Colonel Russ Spicer, Commander 357th FG

A Speech Worth Dying For by C. V. Glines

Those who served with him remember that big, mischievous grin under the wide, thick mustache, the close haircut, and the ever-present pipe. Equipped with a fabulous memory for names, Maj. Gen. Henry Russell Spicer was known as “Hank,” “Russ,” or “Pappy,” depending on when and where you served with him.

For those who were prisoners of war with him in Stalag Luft 1 at Barth, Germany, in World War II, he is remembered as the senior officer in the North No. 2 Compound, the one who went to great lengths to antagonize his German captors and make them adhere to the Geneva Convention in their treatment of POWs. Spicer, then a colonel, once was accused of inciting the camp to riot with a speech he gave to the 1,800-man compound., He received a German death sentence for that speech and thus became an enduring part of the lore of the Air Force.

Spicer graduated from the Army Air Corps advanced flying school in 1934 but had to remain a Flying Cadet for another year because the service was short of funds to commission new flying officers. He was later assigned to fighter units at March Field, California, and Wheeler Field, Hawaii, before becoming an instructor at Randolph Field, Texas, in 1941.

Spicer’s fighter background was evident to those of us who were flying cadets at Randolph in the summer of 1941. As our flight commander, he gave us the all-important forty-hour flight checks in BT-14 basic trainer. You knew you passed if, after demonstrating your skills, he would say, “OK, Mister, I’ve got it” and then put on a demonstration of aerobatics stretching the BT-14 to its limits. You knew you flunked if he merely took over and returned to the field.

Spicer’s skills made it inevitable that he would get into combat in fighters. He was assigned to Eighth Air Force as executive officer to the 66th Fighter Wing and then took command of the 357th Fighter Group in February 1944. He was in England only a short time and had led only fourteen missions, with three enemy aircraft destroyed, when his Mustang was damaged by flak March 3, 1944.

Spicer bailed out into near-freezing waters of the English channel and drifted for two days in a one-man dinghy. Rescue boats and aircraft couldn’t find him. His feet and hands were badly frostbitten when he finally drifted ashore near Cherbourg, France. Unable to walk and near collapse, he was found lying on the beach by some German soldiers. He was taken to OBerursel, near Frankfurt, for interrogation and medical treatment before being sent to Stalag Luft 1.

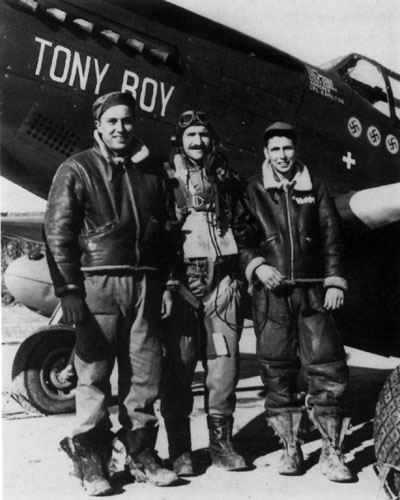

Col Spicer on the wing with (L) Crew Chief SSgt Currie and Armorer (M) Cpl Hamilton. P-51B, “Tony Boy”, G4-H, 43-6880, was named for Col Spicer’s son Tony.

Unintimidated

The Germans didn’t know what a strong-willed person they had on their hands. He was not about to be intimidated or give any information of value, especially names of anyone who might later become a POW. He was questioned by Hans Scharff, a master Luftwaffe interrogator who spoke excellent English and later became a US citizen. Scharff admitted that Spicer was expert at dodging his questions and made a fool of him.

Spicer was still suffering from frostbitten feet and hands when he arrived at Stalag Luft 1. Lt. John J. Fisher, a fellow POW, recalls him lying on his back for long periods, rubbing his legs to restore the circulation. Lt. Richard McDonald, who walked the perimeter of the compound with him, recalls how Spicer had set himself a rigorous rehabilitation program, determined to regain full use of his legs and the ability to walk normally.

Gerald W, Johnson, then a major and one of the top aces in the European Theater of Operations, was a fellow POW. He recalls spending many hours with Spicer playing chess. Sometimes a game would go into a second day, the two not exchanging a word. Spicer also played Parcheesi by the hour, umpired softball games, and was said to have taken up knitting to keep his mind off the pain in his feet.

Even before his feet healed, however, Spicer began to give his captors trouble. New POWs gave him news of the war and told him about atrocities that had been documented. Greatly affected by this, he organized a program of resistance and took every opportunity to harass the guards and cause as much trouble for them as he and his fellow prisoners could get away with. They paid for it with frequent “appell” (roll call) turnouts in the middle of the day when they would have to stand in formation while the “goons” and the “ferrets” went through their barracks looking for anything they said was illegal to possess.

Capt. Mozart Kaufman, who wrote a book about his experience as a German POW, said, “We felt it was a small price to pay.” He added that he regarded Spicer as a good example of a commander – one who kept morale high by challenging the Germans every chance he got. This helped the whole compound maintain a feeling of solidarity against the enemy.

The Speech

On the very cold morning of November 1, 1944, the entire prison camp population had been rousted out of barracks for a required daily roll call, usually a fifteen minute procedure. “The Germans kept us there shivering for an unusually long time,” recalled one POW, Lt. Phillip Robertson. “claiming that they weren’t getting the correct count.”

Robertson went on, “After about two hours, Colonel Spicer dismissed us, over the loud protestations of the German guards. He then called us over to his barracks, and we gathered around him, standing on the ground, as he stood on the steps about three feet above us and began to talk loud enough for the guards to hear.”

In his postwar book, Fighter Pilot, Captain Kaufman recalls what Spicer said:

“Yesterday an officer was put in the ‘cooler’ for two weeks. He had two counts against him. The first was failure to obey an order of a German officer. That is beside the point. The second was failure to salute a German officer of lower rank.”

“The Articles of the Geneva convention say to salute all officers of equal or higher rank. The Germans in the camp have put out an order that we must salute all German officers, whether of lower or higher rank. My order to you is salute all German officers of equal or higher rank.”

Then he got to the real point, saying, “I have noticed that many of you are becoming too buddy-buddy with the Germans. Remember we are still at war with the Germans. They are still our enemies and are doing everything they can to win this war. Don’t let them fool you around this camp, because they are dirty, lying sneaks and can’t be trusted.”

“As an example of the type of enemy you have to deal with, the British were forced to retreat in the Arnmhem area. They had to leave the wounded in the hospital. The Germans took the hospital and machine-gunned all those British in their beds. In Holland, behind the Germans lines, a woman with a baby in her arms was walking along the road, evacuating the battle zone. Some British prisoners were passing her. She gave them the V sign. A German soldier saw her and without hesitation swung his gun around and shot her on the spot.”

“They are a bunch of murderous, no-good liars, and if we have to stay here for fifteen years to see all the Germans killed, then it well be worth it.”

Loud cheers arose from all the men. The German major in charge of the guards was furious. Within a short time, Spicer was put in solitary confinement in the “cooler,” a small cell that measured about six by eight feet. Meanwhile, Kaufman, sensing that Spicer had just made a speech that should be remembered returned to his barracks and began, with the help of his roommates, to reconstruct Spicer’s words. He recorded them in a logbook, which he then buried under the barracks in a tin can.

The Sentence

Spicer was hauled away for a court-martial, charged with inciting prisoners to riot. Later, his fellow prisoners learned he had been convicted and sentenced to serve six months in solitary confinement and then be executed by a firing squad. Spicer was returned to the cooler to serve his sentence while awaiting the execution order.

Occasionally, some of his men would be led by guards past the building in which he was incarcerated, and they would shout out words of encouragement. Robertson recalled, “Then we would hear Colonel Spicer shout back, ‘Keep fighting! Don’t give in to the bastards!’ “When asked if he need anything, he always replied, “Yeah, send me machine guns!”

In the end, Spicer managed to evade the firing squad – by a single day – and the death sentence was never carried out. Shortly before Stalag Lufft 1 was overrun by Soviet troops on the night of April 30, 1945, the German guards fled and left the prison camp unattended. When a fellow prisoner awakened Spicer and told him they had been freed, Spicer wouldn’t leave. “I have one more night to make it an even six months,” he explained. “I’m staying here tonight.”

When Spicer finally did come out, according to Robertson, “Every prisoner – to the man – gathered at the entrance to greet him, cheering an trying to pat him on the back. He gave a short speech and said that seeing us and hearing our shouts made the whole experience in solitary confinement worth it.”

In the next few days, Spicer was evacuated with the 6,250 other former “kriegies” and flown from Barth to Camp Lucky Strike in France for processing before going home. Colonel Spicer, who later became an Air Force major general, retired in 1964 and passed away in 1967, but he will always be remembered for the speech that not only brought him a death sentence but also brought strength and fortitude to his fellow prisoners.

Thanks to Tony Spicer, Colonel Spicer’s son, for providing this information on his father.

Colonel Spicer with Sgt Currie (L) and Corporal Hamilton

Read the Speech Colonel Spicer gave fellow POWs.

Col. Spicer’s Speech

Morning roll call was over. The German Officer, Major Steinhauer had given the Colonel permission to dismiss the Group. Before dismissal he ordered the men to assemble in front of Block 7.

“Lads, as you can see this isn’t going to be any fireside chat.”

“Someone has taken the steel bar off the south latrine door. The Germans want this bar back. They have tried to find it and we also tried to find it. We have had no success. The Germans have threatened to cut off our coal ration if this bar isn’t found by 12 noon. I don’t know if this is a threat or not, but we must return the bar to the Germans. Anyone having any information report to my room after this talk. There will be no disciplinary action taken against anyone.”

“Yesterday, an officer (Major Bronson) was put in the cooler for two weeks. He had two counts against him. The first, was failure to obey the order of a German officer that is beside the point. The second was failure to salute a German officer of lower rank.”

“The Articles of the Geneva Convention say to salute all officers of equal or higher rank. The Germans in this camp have put out an order that we must salute all German officers whether lower or higher rank, my order to you is salute all German officers of equal or higher rank. I have noticed that many of you men are becoming to buddy buddy with the Germans. Remember that we are still at war with the Germans. They are still our enemies and are dong everything they can to win this war. Don’t let him fool you around this camp, because he is a dirty lying sneak and can’t be trusted.”

“As an example of the type of enemy you have to deal with, the British were forced to retreat in the Arnheim area. They had to leave the wounded in the hospital. The Germans took the hospital and machine gunned all those British in their beds.”

“In Holland, behind the German lines, a woman with a baby in her arms was walking along the road evacuating the battle zone. Some British prisoners were passing her. She gave them the “V” for victory sign. A German soldier saw her and without hesitation swung his gun around and shot her on the spot.”

“They are a bunch of murderous no good liars and if we have to stay her for 10 years to see all the Germans killed then it will be worth it.”

(Loud Cheers from all the men)

The Colonel then turned to the German Major and Non-Coms standing at the side. “For your information, These are my personal opinions and I’m not attempting to incite riot or rebellion. They are my opinions and not necessarily the opinions of the men”

(More loud Cheers)

Then facing the men again, “That is all men and remember what I have told you.”

Within several hours the Colonel was in solitary confinement and Lt Col. Wilson next in command had been threatened with solitary confinement the next day if the crow bar did not show up. Colonel Spicer was put in solitary and did not get out until midnight of April 30, 1945, when Americans took over the camp. He was court marshaled and sentenced to death to take affect in three months. This was the last of Dec, 1944 and April the 1st, 1945 things were so hot in Germany, that the sentence wasn’t carried out.

This speech was recreated by Mozart Kaufman, who was with Colonel Spicer in the POW Camp. He was standing 23 inches in front of Colonel Spicer during the speech and immediately afterwards reconstructed the speech with fellow POWs “word for word.”

Links about Stalag Luft One:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stalag_Luft_I

https://www.b24.net/powStalag1.htm

Allied aircrew shot down during World War II were incarcerated after interrogation in Air Force Prisoner of War camps run by the Luftwaffe, called Stalag Luft, short for Stammlager Luft or Permanent Camps for Airmen.

Germany held nearly 9,000 USAAF and RAF airmen at Stalag Luft I during WWII. Stalag Luft I was located two miles northwest of the village of Barth, Germany, on the Baltic Sea. The first Allied prisoners entered the camp on 10 July 1940 (French and British POWs). The German garrison left the camp several days before the arrival of Soviet forces on 2 May 1945. The POWs were evacuated by 8th Air Force B-17s on 12-13 May 1945.