357th Fighter Group 362th Fighter Squadron ‘Yoxford Boys’ P-51B Mustang Named “Joan'”

A TALE OF TWO P-51S NAMED “JOAN”

By Merle Olmsted

This is the story of two obscure P-51s, among the hundreds of colorful fighters of the old 8th Air Force of WW II. Both aircraft scored victories over the Luftwaffe; one was part of the 8th Air Force’s historic first bombing raid on Berlin; one flew a shuttle mission to Russia, and one was flown by an eight-victory ace.

The author was a ground crew member on both these machines, and for many years thought he knew the correct sequence of events that befell the two P-51s. Almost 50 years later, with new information and reanalysis of the memory bank and available photos, he discovered he had been wrong on many aspects of the story. Hopefully the following is the correct story of these two obscure P-51s.

When the 357th Fighter Group formed at Hamilton Field, California, in late 1942, this writer was assigned as assistant crew chief, with Staff Sgt. Ray Morrison as crew chief. CC slots were usually given to the “older” men in their 20s, while the kids, not yet 20, were made assistants. Morrison and I worked together as a team from Hamilton Field days until the end of the war, first on P-39s and then on P-51s. Only a handful of the maintenance men were old-line army NCOs; the rest of us were fresh out of Air Force mechanics school, the same being true among the newly arriving pilots.

Following is the story of the first two P-51s assigned to us upon arrival at 8th Air Force Station F-373, near the town of Leiston in the eastern bulge of England. These first two Mustangs were B or C models (the same airplane built in Inglewood or Dallas). Although the author took several photos of “his” first aircraft, none showed the tail number, essential to its identification.

“Swoose” (A cartoon character at the time.) This is P-51C, 42-103007. G4-P. There is no other photo of it with this name. It soon became “Joan.” The men in the photo are Harry Baily, left, armorer, and Ray Morris, Crew Chief. This airplane was wrecked in a ground accident, rebuilt and transferred to another group.

The First Joan

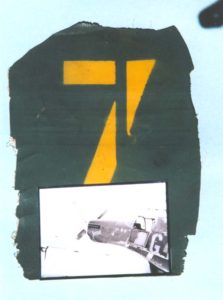

One photo shows the crudely painted name Swoose (a cartoon character) on the engine cowl. I have no idea where the name came from. Memory told me that this first P-51 was badly wrecked in a ground accident at a very early date and was replaced by a second P-51B, serial number 42-106829, which was documented with photos. When the first B model was wrecked, the writer cut a large number seven, in yellow on olive-drab fabric, from the rudder. This fabric lay in an album for almost 50 years before it was realized that it could be a clue for the aircraft’s identity.

Rudder Fabric cut off a wrecked P-51 by Merle Olmsted in 1944. According to Merle, this should be very close to the original shade of Olive Drab used on the 357th FG Mustangs at Leiston. He has kept this in an album until recently when he had it framed.

A photo taken in the 362nd Squadron’s operations room, of the operations NCO and the parachute rigger, showed in the background a wall chart of all 362nd aircraft, with their squadron code and the last three digits of their number. All 362nd P-51s carried the code G4 with an individual letter for each aircraft, ours being “P”, hence G4-P. The chart showed P’s last three numbers to be 007.

A search of P-51B and C serial numbers brought up three aircraft ending in 007. Charles Worman, historian of the Air Force Museum at the time, provided enough information to eliminate two of these, proving that our “mystery Mustang” was serial 42-103007, which in turn indicated that it was a Texas-built P-51C-1.

The now available individual aircraft record card showed that 007 had been delivered to the AAF at North American’s Dallas plant on 23 October 1943, and six days later was ferried to a modification center at Buffalo, NY. The record card does not say for what reason, but it was almost surely to have the 85-gallon fuselage fuel tank installed. The small white cross, indicating the presence of the tank, which was painted under the aircraft data block on the left side, would later prove useful in identifying the P-51 in photos in which the tail was not visible.

On 13 December 007 was flown to Newark, NJ, and departed the US in a crate. By the 5th of January 1943, it had arrived at the huge processing depot in northern England, and probably arrived at Leiston airfield 10-12 days later, in time to fly the group’s first operation.

Availability of individual aircraft record cards, and AAF accident reports, made it possible to complete the story of the two P-51s. The accident reports on 007 provided the date of the ground incident, 10 April 1944, considerably later than memory told me.

Before this, 007 had flown between 15 and 20 missions, though there are no records to provide such information. As stated, its squadron code was G4-P, painted on both sides of the fuselage in 8th Air Force manner. The assigned pilot was 2nd Lt. Robert Wallen who flew the aircraft on the 8th AF’s historic first raid on Berlin, on 4 March 1944. (Actually the first U.S. fighters over Berlin were P-38s of the 20th Fighter Group on 3 March. The weather was miserable, and the P-38s arrived over Berlin to find no bombers, which had been recalled.)

On 4 March the 357th was among the first single-engine fighters to escort bombers to Berlin. Though some 20 German fighters made one pass through the bomber formation, there was little combat. The 357th scored two victories: one by the later famous Chuck Yeager (his first) and the other by Bob Wallen in 007. (Five other kills were credited to the 4th, 354th, and 359th Fighter Groups. BT)

Wallen had named his plane Joan, presumably for a girlfriend, though the woman he married after the war was Margaret. The name was painted on both sides of the cowl, first in white, then in yellow, several different times in different styles, most done by this writer. During that time the aircraft was in the standard OD/gray paint with a white nose. After about 1 April it would have had the red and yellow nose markings the 357th carried for the rest of the war. As indicated, none of the photos taken by this writer show the tail number, now considered an inexcusable omission! Though Wallen did destroy an FW-190 on the ground later on, no explanation for the second victory symbol at this early date can be found. (Wallen might have had an unconfirmed claim or the victory possibly belonged to a pilot who usually flew another Mustang. BT)

Four days after the Berlin mission, 2nd Lt. Bryant Anderson flew Joan on a radio relay mission. When the group’s P-51s were deep in Germany their SCR-522 radios did not have range to contact home base, so one or two P-51s were assigned to orbit just off the enemy coast at high altitude to relay messages from, and to, the group leader. Upon returning from this mission, Anderson made a bad landing, damaging the propeller. Anderson had only six hours in P-51s, and 007 had about 50 hours total time. The damage was minor.

There are no records to indicate any special occurrences for the next month. The group flew 12 missions during that period, including two more to Berlin, and Joan would have flown most of them.

After the mission to Rostock on 9 April, 007 was due for an inspection. Normally the crew chief and assistant accomplished this on the aircraft’s hardstand, but if the night hangar crew was not busy with engine changes or major maintenance, they would do the inspection during the night, as in this case.

The next morning, 10 April, Morrison went to the hangar and, finding the night work complete, he started the engine and began taxiing to the hardstand about a mile away, this writer following on a bicycle. Following Morrison in Joan was Staff Sgt. Avery Goodrich in Shanty Irish, for which he was crew chief.

Upon arrival at the hardstand, near the control tower, Morrison slowed to a stop to unlock the tailwheel and turn into the parking spot. Goodrich was aware that Morrison was ahead of him and stated in the accident report, “I started to my hardstand, essing all the way, watching for anyone standing by to signal me on. I passed several men on the way, but no one signaled me that the other plane was stalled on the taxiway. The first thing I saw was a tail of a ship in front of me, but I could not stop before I hit the other plane.”

The propeller of Shanty Irish destroyed the tail section of Joan. Shanty Irish required a prop and engine change and repairs to one wing. Lt. Gilbert O’Brien went on to fly it to the end of his tour and became an ace in it (serial 43-6787, G4-Q). After another ground accident much later in the year, it was rebuilt as a two-seater, survived the war, and was salvaged in the summer of 1945.

The accident board put the blame on Goodrich, and he was punished by one week of “hard labor” in addition to his other duties. The “hard labor” turned out to be doing yard work around the squadron orderly room, after which he continued his duties as a highly regarded crew chief.

It is believed that Joan returned to flying missions after repairs, but it’s uncertain. “Double Oh Seven” had flown about 15 missions, at least two to Berlin, and shot down one (possibly two) enemy aircraft. Sometime after the repairs, around 1 May, 42-103007 was transferred to the 496th Fighter Training Group at Goxhill in the north part of East Anglia. Goxhill is where all incoming fighter pilots went to transition into one of the three types of fighters used by the 8th.

As an indication of how little things can help in identifying aircraft, the particular P-51 had the required small white cross on the left side of the fuselage, just below the data block (indicating installation of the 85-gallon fuselage tank), but this cross is out of its proper position and slightly distorted, making it possible to identify the airplane even when the tail and codes are not visible.

007 shows up again on the accident record at Goxhill on 31 May 1944, where it suffered some minor damage and was returned to service.

On 7 June two P-51s took off from Goxhill on solo instrument training flights: 2nd Lts. Robert Magnasun on P-51C (42-103036) and Charles R. Moritz (42-103007). The weather was cloudy and somehow the two aircraft collided. Lt. Magnasun stated that he never saw the aircraft that hit him. With the right wing torn off, he bailed successfully. Lt. Moritz was unable to get clear and died in the smoking hole that 007 made in the English countryside. It had been Moritz’s first flight in a Mustang.

The following statement from the accident report is of interest. “After investigating the accident, the only evidence found to give positive proof of this being the P-51 flown by Lt. Moritz was the rudder which had a number 3007.” (The first four digits were on the vertical stabilizer.)

By a strange twist of fate, the yellow number 7, from the aircraft’s original rudder, is hanging on the wall of my office as this is written 59 years later.

So ends the cradle to grave story of the first Joan.

The Second Joan

With the loss of the first Joan, for a new tail, and her transfer to the training establishment, Morrison and Olmsted were out of a job. Until assigned a new aircraft, the usual practice was for the idle crew to assist other crews where needed. It was during this period that the author was sent to an RAF school in northern England, on the Merlin engine.

The replacement for 007 was P-51B-15-NA, serial 42-106829, built at North American’s home plant in Inglewood. Delivered to the AAF at the factory on 26 February 1944, it departed Long Beach airport on 4 March, bound for Newark, NJ. The ferry flight from Long Beach to Newark took two weeks, much longer than usual.

The aircraft record card is garbled, but it seems 829 was delayed at several points by weather and “waiting for a pilot.” It finally arrived at Newark on 24 March and departed the US on 5 April, either crated or as deck cargo. It was at sea when the first Joan lost its tail on the 10th.

All US aircraft entering Britain by sea were processed through one of three giant base air depots, of which the major ones were BAD 1 at Burtonwood and BAD 2 at Wharton, both near the coastal city of Blackpool on the Irish Sea. Wharton, with over 10,000 employees, was responsible for P-51s, with over 4,000 Mustangs (and 2,800 B-24s) passing through these facilities during the war.

Among the 4,000-plus P-51s was 42-106829, which arrived at Blackpool about 17 April. It appears as though P-51s spent about ten days at Wharton before being delivered to their operational units. 829 would have arrived at Station F-373 (Leiston) late in April.

December 1943 marked the end of camouflaged P-51s. The AAF had come to the conclusion that the benefits of camouflage were not worth the effort, cost, and time to apply. All P-51s leaving the plants in California and Texas after 1 December 1943 were bare metal, including 829.

In the fall of the previous year, identification bands were ordered for P-51s arriving at the processing centers in England, due to the airplane’s resemblance to the Me-109. The bands, in white, were applied to the vertical and horizontal stabilizers, inboard on the wings, and the aircraft nose was painted white forward of the exhausts.

With elimination of camouflage, the bands were still called for, but now in black. Photos taken at Wharton show bare metal P-51s with these markings. One, serial 42-106835, is only six digits from our 829.

There are many publications with long lists of 8th Air Force fighters providing the aircraft’s name, tail number, pilot, and unit codes. None is complete, or even very accurate, including those by the author. It would have been difficult to keep up with the rapid changes at the time, even if anyone cared, and is beyond the realm of possibility today. But the lists are useful as long as their limitations are realized.

P-51s of the 357th Fighter Group went through a surprising number of appearance changes as paint was applied, removed, then reapplied, often in a different scheme. Historically this was a very interesting period, but group records are totally silent on the subject. The writer has a filing cabinet full of 357th records, but none mention painting or changes in schemes.

Therefore, the subject of appearance changes must be done by deduction from the study of photos and “feel” for the subject. Approximate dating of any photo can often be done by the presence or absence of one of the two types of drop tanks, the nose colors, invasion stripes, Malcolm hoods, etc. Knowledge of the various 8th AF directives, and their date of issue, is also useful.

On arrival of the shiny new P-51 at the 357th’s base, it would have gone to the 362nd Squadron hangar for an acceptance inspection, and for Staff Sgt. Louis Bourdreaux, the squadron painter, to apply the red and yellow nose colors and the new codes, G4-P.

It would now be early May. The biggest event in the European war, the invasion of the continent, was only one month away.

The newly painted aircraft was assigned to the same crew and pilot as the previous Joan, Morrison and Olmsted and pilot Bob Wallen. At Wallen’s direction the author gain painted Joan on both sides of the cowl.

Sometime in mid-May 8th Fighter Command dispatched a message to all groups, suggesting that aircraft which might be based on the continent should be camouflaged. According to tentative plans, this would have meant all of them.

However, the results of the message suggest that Fighter Command provided few details, leaving it up to the groups. This resulted in a great variety of new paint schemes throughout the command. Some groups seemed to ignore it while others complied in their own unique way.

At Station F-373, apparently each of the three squadrons decided on a different approach. Some aircraft remained bare metal, some were painted completely in RAF green and gray, and some received an attractive scheme which the author calls “the half paint job.”

In the 362nd Squadron all three methods were used; in the 363rd nearly all their P-51s were fully painted in green and gray. The 364th followed the 362nd method but with fewer of the “half” scheme.

From photo evidence, 12 P-51s of the 362nd Squadron were painted in the half scheme and half a dozen in the 364th with none in the 363rd.

At this point we are presented with another minor mystery. Among the author’s photos is a P-51B in the half scheme but carrying 75-gallon drop tanks which would suggest a date before 1 May when the 108-gallon tanks were cleared for use, and before the suggestion that all fighters be painted.

Joan was one of those painted in the attractive half scheme, but it is not known if this was done at the time of its arrival or later in the month.

In the meantime, Wallen had destroyed another enemy aircraft while flying Joan. On 30 May the mission was usual bomber escort, during which the 357th engaged in combat with three groups of German fighters, claiming 18 with one loss. Wallen had attacked and overshot an Me-109 which was shot down by his wingman, Lt. Lloyd Mitchell. Separated during the melee, Wallen was on his way home alone at low altitude when he spotted a small airfield with one hangar and a lonely FW-190 parked in front of it. Wallen fired a long burst into the 190 and left it burning.

As D-Day grew closer, the famous order to apply the invasion stripes came in, so it was back to the paint guns and brushes again. Since the big day was originally planned for 5 June, the stripes may have been painted on the night of the 4th, or possibly on the 5th due to the one-day delay. Since Staff Sgt. Boudreaux and other squadron painters would have been swamped, the ground crews painted many of the planes using brushes. The author has a vague memory of doing so with the aid of a flashlight.

On D-Day, 6 June 1944, the 357th flew eight missions, the first taking off at 0215, led by Colonel Graham, and not returning until 1015—a very long mission but unproductive as no enemy aircraft were seen. Three pilots were lost during D-Day missions.

Bob Wallen and Joan would have flown two or three missions at which time the aircraft had about 25 mission symbols painted on its side.

During the two months between D-Day and early August, the group continued flying, often two or three times a day, except for 11 days during a “stand down” providing rest for the pilots and a chance for the ground crews to catch up on deferred maintenance. Also during this period, Joan had one of the highly prized Malcolm hood canopies installed with a “Spitfire” mirror over the windshield.

The next big event for the group was the shuttle bombing mission to Russia, on which the 357th escorted the 13th Bomb Wing to Russia, Italy, and back home. Wallen and Joan were part of the adventure on 6 August as Colonel Graham led 72 Mustangs on a seven-hour flight to Russian bases (seven P-51s were spares and returned to Leiston.) They flew one escort mission from Russia and then flew on to Italy before returning home on 12 August. One P-51 was lost in a nonfatal accident, and six German fighters were shot down during the odyssey. On the last leg of the flight from Italy to England, a U.S. Mosquito was tragically shot down when mistakenly identified as a Ju-88.

P-51B Joan 42-106829

By now Joan had flown about 40 missions, and 1st Lt. Robert Wallen had finished his combat tour. Sometime in August or September he departed for the Zone of the Interior. A new pilot and a new name for 42-106829 were in the works.

Dittie Jenkins and Floogie.

In the latter part of August, Flight Officer Otto D. Jenkins was among a group of replacement pilots that checked into group headquarters, then to the 362nd Squadron. As a “new boy” he was given the now elderly P-51B, 829. Somewhere along the line he had acquired the nickname “Dittie,” though his family never called him that.

Again there is no exact date, but about the time of Jenkins’ arrival, 42-106829 was again painted, this time in full OD and gray. (It probably was RAF green but OD seems to photograph lighter, and the only photos in this paint look like OD). At this point the trend was toward bare metal again, so why it was painted in obsolete camouflage is unknown.

For the last time, the writer painted a name on 829, this time Floogie, in yellow. It was Jenkins’ pet name for his wife.

In the vernacular of the times, Jenkins was a “hot pilot,” scoring his first victory only a week or so after his first mission. On 13 September he shot down an Me-109 and shared another with his friend (also a new arrival and future ace), John Kirla.

Six days later, on 19 September, Jenkins reported: “I was flying element leader in Dollar (362nd FS) White Flight when we approached a dogfight. Two Me-109s came by in formation so my wingman Lt. Perry took the one on the right and I went after the one on the left. I closed to about 300 yards at 4,000 feet altitude, doing 300 mph IAS, and began to fire. I saw many hits on wing roots, canopy, and wings. The plane exploded and went into the ground. I saw no parachute.”

Having lost the rest of his flight, Jenkins then spotted an FW-190 flying alone a railroad track, and gave chase. As he closed in, the 190 pulled up, did a roll, hit some trees and exploded. Jenkins had not fired a shot but achieved a victory nonetheless.

His last victory in 829 came on 6 October when he shot an FW-190 off the tail of his element leader, Lt. William Mooney. In his encounter report, Mooney verified the victory and ended by saying “He proved to be a very capable wingman, F/O Jenkins did.” Neither Mooney nor Jenkins would survive the war.

Jenkins probably scored 4.5 victories in Floogie.

Three days later, on 9 October, the mission report states, “One pilot Not Yet Returned. F/O Jenkins, 362nd Sqdn, belly landed Brussels at 1615 (safe). Reason unknown.” (It was engine failure.) An amendment to the report says, “10 Oct, F/O Jenkins returned to base.”

The aircraft record card on 42-106829 states it was salvaged on 30 November 1944. Apparently she had lain in the Belgian field until the 9th AF salvage unit could get to the job, then she was junked. (Like her predecessor, she had flown for about seven and a half months. BT)

Jenkins and the same ground crew were then given a new D model in RAF green which survived until January 1945 when it was lost with another pilot in a fatal weather accident. It had been Floogie II. Jenkins then flew another D model named Toolin’ Fool’s Revenge, but with another crew, to complete his combat tour in March with 8.5 victories.

Having survived some 300 hours of flying in the deadly skies of Europe, Jenkins returned from his final mission on 28 March 1945. In his exuberance he buzzed the squadron operations at very low level. On his third pass he pulled up, did a split-ess, hit a tree on pullout, and crashed in a huge ball of flame.

Like many others on Station F-373, this writer was a witness to the disaster.

The accident board had no choice but to list the cause as “100% pilot error.”

We have told the tale of two P-51 Mustangs “from the cradle to the grave.” Between the two of them, one was among the first single-engine Allied fighters over Berlin and shot down an enemy aircraft on that historic date; was over the beaches of Normandy on D-Day; was on the first shuttle mission to Russia, and shot down 5.5 enemy aircraft (possibly 6.5) Not a bad record for two obscure P-51s among the 10,000 that rolled out of the North American factories.

Their story is probably little different than that of hundreds of others, but they are unique in that we have been able to follow them through their life spans.

Presented with permission from Merle Olmsted and the American Aviation Historical Society.