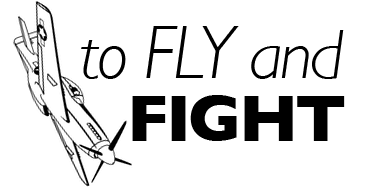

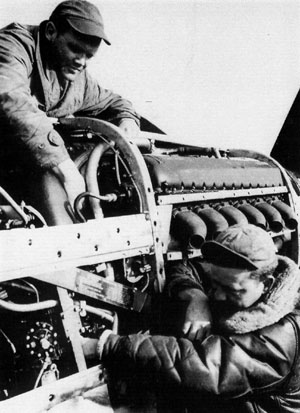

A typical flight line crew at work: the armorer is deep in the gun bay, and the crew chief appears to be washing down the engine compartment with gasoline and a spray gun. The bucket is visible on the cowl, and the trailer mounted air -compressor is at left. This P-51B was squadron code B6-Z, and carried the name “Doodle Bug”. It’s serial number was 42-106458 and was flown by John Skara of the 363rd FS

A View From the Flight Line – A Personal Memoir

by Merle Olmsted with Willard Bierly and Joseph Deshay

Vast columns of words have been put to paper on the subject of aviation history, and especially that of the wide-ranging conflict of WWII. Few of these words make reference to the little matter of aircraft maintenance, or the aircraft mechanics. Hundreds of in-depth articles and books have poured forth on airplane types and unit histories, their writers going into great detail about the development problems and solutions, the designers, the test pilots and the test programs then into operational service, and the pilots who fly them. Most of the exhaustive tomes say nothing whatever about maintaining the birds once they are in squadron service. Presumably, after reaching the operational phase, they are now perfect and require nothing more, other than a swipe across the windshield.

This of course, is a gross distortion of history for those who read it now and in the dim future. The military airplane is a very cantankerous piece of machinery. Frequently there is something wrong wit it, and the frustrated mechanic (read fitter or rigger for our British friends) must decide what it is now that has gotten out of order. He must then fix the damn thing, often under less than ideal conditions, and hopefully have it serviceable again by the time Operations demands it’s availability.

It is easy of course, to see why writers ignore the subject. Some have had no personal contact with the aviation world, but it is also true that aircraft maintenance is totally without glamour, and it is always accomplished by those lowest on the military ladder – the enlisted man. Fixing airplanes is usually drudgery, uncomfortable, and almost always dirty work, at least in the days of the piston engine. All of this makes it difficult to write about, and history writers can perhaps be forgiven for ignoring the subject.

Nevertheless, the aircraft mechanic has been absolutely vital for the roughly 90 years of heavier-than-air flight – no one will fly for long without him. For that reason alone, it is hoped that future writers will give him a mention now and then, or acknowledge his existence.

None of the above is meant to, in any way, reduce the credit or attention given to the flight crews. The man on the ground who maintains the machine is the greatest admirer of the combat crews who fly and fight “his” airplane.

This effort might also have been titled “Before the memories fade,” but it is already too late for that. In the area of California where I reside, we have a larger group of ex-WWII Air Force types, ranging from general to sergeant. Informal “Kaffee Klatches” are frequent, at which a common theme is how much we have forgotten about those long-gone times. To the question, “Do you remember so-and-so?” I often must admit I do not recall the occasion, prompting my good friend and neighbor Will Bierly to ask if we were in the same war, to say nothing of the same fighter group.

Nevertheless, we will press on with this “view from the flight line,” in hopes that some of what we do recall will be of interest or use to those who care about the great air war of 1939-1945.

To do this, I have badgered tow of my associates of that period to put their memories on paper, and provide some thoughts on the mechanic’s view. The three of us were very fortunate in many respects. Being in a non-combat job, we came through unscathed. Yet it provided an experience that probably was the high point of our lives, although we did not know it at the time.

In addition, we were lucky enough to serve with one of the most successful fighter groups of the old Air Force. Most air veterans of the period think their unit was the best, as they should, but we believe the statistics bear us out. Even so this is not an operational history of The Yoxford Boys, the 357th Fighter Group, and we will touch on that aspect only incidentally. The history of the group is available in several fine books on the USAAF’s 8th Air Force.

Although this memoir is presented by a hangar chief, an armorer and a mechanic, there were numerous other specialties whose efforts were also vital to success and who were all part of the generalization labeled “ground crew.” To refresh our fading memories, we have referred to several technical orders and manuals to provide some technical tidbits which might be of interest to those so inclined. These included the North American factory flight manual on the P-51B and C, the Army Air Force pilots’ handbook on the D&K, the AAF Fighter Gunnery Manual, and the servicing handbook for the V-1650 engine.

Joe Deshay was from upstate New York when the war came along, and already married to Ellen, still his copilot as he calls her, at the start of the 1990s. As editor of the 357th Association’s newsletter, he is what holds the veterans of the 357th together. Joe held the highest rank of the three of us, and as a master sergeant, was at different periods a flight chief and a hangar chief of the 364th Squadron. (Incidentally, the 364th did not have a real hangar! The engineering officer of my squadron, the 362nd, was on scene first, and grabbed the only hangar available to the squadrons, a big metal RAF Type T-2. The other tow squadrons had to make do with the small blister hangars, which were open on both ends except for canvas covers. Each house three P-51s.)

Rank has its privileges (the old RHIP) and Joe will be element leader on this project.

The aircraft mechanics who served in the Army Air Forces of World War II, who were to be part of tactical units, were normally assigned to a squadron and performed their duties in a section known as “Engineering,” a term long since abandoned.

After completing basic military training, it was normal for potential mechanics to be assigned a four-month technical school, such as those at Lincoln, Nebraska, or Biloxi, Mississippi, where these two schools trained men in the basics of aircraft and engine maintenance and repair. Eleven different phases were taught, such as fundamentals, structures, hydraulics, propellers, instruments, engines, electrical systems, fuel systems, engine operation, and tow phases of aircraft inspection.

After the completion of this A and E schooling, some of the men went on to specific manufacturing plants where one month of courses were presented by the civilian instructors of the company, such as the Bell Aircraft School at Tonawanda, New York, or P-38 school at the Lockheed plant in California. After this, some men went on to further schooling at various engine builders’ plants. Others who were to be specialists went on to courses on propellers, instruments, etc. Upon completion of all this learning process, the men began to come together in a squadron where their training skill would be put to use.

Our home was to be the 357th Fighter Group, consisting of three squadrons, the 362nd, 363rd and the 364th. Organization of the unit and assignment of personnel took place at Hamilton Field, California, in the San Francisco Bay Area, in the early months of 1943.

Our aircraft was the P-39 Airacobra fighter, manufactured by the Bell Aircraft Company. After organization, the group acquired their aircraft and began flight training at the Bombing & Gunnery Range, Tonopah, Nevada.

It was at this time that the “book learning” was put to use, and practical experience for all men of the squadrons began. In order for the pilots to be trained in all aspects of flying this “hot” new fighter, the flying time put on the aircraft was excessive. The airplanes were flown so much, including some night flying, that much of the repair and maintenance had to be performed at night.

As the flying hours accumulated, on form 1 and 1A flight report of each aircraft after 25 hours, 50 hours and 100 hours, specific inspections were required as well as any repair work that needed to be cared for. An engine that had accumulated 500 hours of flight time had to be removed and sent to the depot for overhaul. An engine change required many hours of work by the mechanics and specialist. By using as many men as practical to work on any one change, we were not able to complete an engine change in one day.

After training at the Bombing & Gunnery Range, the squadrons were separated and assigned to small air bases in the west where training conditions permitted more pilot training, with group headquarters located with one of the three squadrons.

Even today, the mechanics love to reminisce about an incident that took place late at night on a hard stand at Santa Rosa Army Airfield. Potentially deadly, it is regarded now as a humorous story. We were performing a 100-hour inspection on a P-39, and one of the many inspections called out by the tech order was to “swing the landing gear.” This required jacking up the four-ton bird so as to send the main gear and the nose gear through the raising and lowering cycle to check operation, smooth closing of the covering surfaces with gear up, check warning lights for UP and DOWN positions, proper locking, etc.

Being very late at night, all sorts of mechanics, armorers, and radiomen were all over that jacked-up aircraft like bees in a hive. In order to swing the landing gear, the battery switch had to be in the ON position. The armorers had removed the 37mm cannon to clean and service it and had just reinstalled the gun. There was ammunition in the ammo can. The armorers then somehow turned on the sun switch and the cannon fired one round. Even though it was a practice round, with blue projectile, it had a tracer compound, and it made a spectacular sight as it went over the farmer’s chicken house and, of course, the unexpected blast got everyone’s attention. This was especially so for a prop man who was working on a tall crew chief stand in front. He had just bent over to retrieve the large half-circle wrench which was used to tighten the prop hub nut. His timing was perfect for survival – while he was bent over the gun fired – right where he would have been in another second or tow. This may have been the only time a 37mm cannon of a P-39 was fired while it was on jacks!

Our time finally arrived to move on to a combat area, and this took us to England, with a change to the North American P-51 Mustang fighter and its Rolls-Royce Merlin engine.

Since we had to wait for aircraft to be assigned to our units, some of the mechanics were hurried off to the Rolls-Royce company’s engine plant at Darby, for a few weeks of schooling. Some went to the Burtonwood Air Depot for P-51 airframe school.

All the mechanics were assigned to the Engineering Section, under the Engineering officer, a first lieutenant or captain, some serving on the flight line as crew chiefs and assistant crew chiefs, working at the hard stands, some of which were the revetment type. Other crews were assigned as hangar crews. Regardless of their assignment, all had the same training background except the specialists, who performed their duties in the hangar areas. Without any doubt, the excessive work that had been done by all the technicians when stateside, exhausting as it was over long hours each day, paid off when combat days arrived, as the crews were well prepared to do the job and establish a fine maintenance record.

The cold and damp winters of England made it most unpleasant to be working on aircraft out in the open. the arched blister hangars provided little protection form the cold and the elements, and it was not practical to work with gloves on.

The prime objective in the combat area was to have all possible aircraft available for the next morning’s missions. This led to considerable work being performed at night when complete blackout was in order to comply with the general blackout in England. A small tow-cell flashlight was usually the most lighting permitted.

The 25-, 50- and 100-hour inspections rolled around fast due to the lengthy escort missions that were the group’s main mission. Engine changes were frequent, provided the aircraft lasted through its hazardous missions. Even though the P-51 with its Rolls-Royce Merlin engine and the Hamilton Standard propeller were three great mechanical machines, failure was bound to happen on occasion. Ground fire and aerial combat created considerable sheet metal work and those specializing in that duty performed some super repair jobs.

As we look back in time, it seems that the closer one’s duty was to the aircraft, there might be a bit more limelight, but without a doubt that is where the long exhausting hours had to be spent. We never seemed to have enough manpower to perform the work that had to be done in the daylight hours. Our fighter group was blessed with a fine group of mechanics. The armorers, ordnance men, radiomen, cooks, clerks, and other specialists all made up a fine team.

My duties as a hangar chief were no different than any supervisory responsibility in any work area. It was best to get to know your men with respect to ability, personality and to assign work to pairs of men on smaller jobs. One had to learn as to who worked well and got along well with the number one man on the job.

We were trained for accident awareness and to take all precautions against possible fire hazards. A clean hangar and a tidy one was a must.

A hangar chief also had to do a considerable amount of troubleshooting and make decisions as to what maintenance to perform when one of the “wild Mustangs” was acting up. Our squadron mechanics were such that we all pooled our thoughts and efforts to “keep ’em flying.” I’m sure this existed with our communication and armament people also. It is my opinion that this attitude is what made our maintenance record for the duration of combat one of the best of all 8th AF fighter groups.

The mechanics, like all good GIs, never stood short on tools and equipment to do the job. If Technical Supply didn’t have it, someone made it. The material to make it from was borrowed or stolen from somebody by means of a “moonlight requisition.” All fighter units which suddenly found that their flight line was to be equipped with P-51s also learned that the Merlin engine was assembled with Whitworth thread nuts and bolts. Wrenches to fit them were in short supply and many had to be made. Clever welders also made other useful equipment.

The terminology of those days and the verbal expressions of the mechanics on the flight line and in the hangar area was a language of its own, nicknames for everything. I still smile today when one of the mechanics referred to his friend, a radio technician, as a “static chaser.”

During the time that I served as a flight chief, I was also on backup for our line chief when he was away on pass or furlough.

I learned that one of the most unpleasant aspects of the line chief’s duties was that he was to be the first man awakened by the CQ (Charge of Quarters) in the early hours on mission days.

The line chief and assistant crew chiefs were billeted in Nissen juts accommodating 14 men. If a crew chief, or his assistant, was to preflight their ship on mission days, they tied a white towel on the foot of the bed, indication to the line chief or the CQ who he was to awaken. You soon learned who you had to go back to shake a second time, and maybe yank the covers off on the third time around!

There was a limited time to roll out of the sack and get dressed in order to catch a ride on the one and only truck parked at the orderly room. If you missed it, there was a long three-mile walk or bicycle ride to our flight line.

If the mission was to be the usual bomber escort, some of the ’17s and ’24s would be overhead already as we preflighted, headed like a swarm of bees out over the North Sea to the continent. The fighters would catch up and join them either on the way in, over the target, or on the way out, whatever the assignment might be.

The line chief and a flight chief had to see that each crew chief got the oxygen service he needed, and that the five fuel tanks were topped off with as much gasoline as possible.

The Merlins’ coolant system was serviced with ethylene glycol, better known by its commercial name of Prestone. It was not pure ethylene glycol, but a mixture containing 70 percent water, the percentage being best for efficient cooling and for its antifreeze properties. To go out to one’s aircraft at its hardstand in the cold of the wee hours of the morning and find a puddle of fluid underneath the engine cowling was most discouraging. It was then off with the engine cowling in a hurry, and check the hoses and clamps and find the leak location and repair it before the pilot’s arrival.

There was a time in the latter part of our combat days when we had a problem with tail wheel tires blowing out on our P-51s as they taxied from the hardstands onto the perimeter track, or onto the runways. At these points a sharp turn was made, which tended to roll the tire off the rim or blow out.

Now it was not for we of the ground crews to determine if the situation was accidental, or if it was created intentionally. However, we did not want to see an aircraft about a mission in this manner, so we assembled a spare tail wheel, complete with tire and tube. We took a team of three men and the Cletrac out to the marshalling area of the runway, and sat waiting for any tail wheel failures., When such occurred, the Cletrac driver ran the machine up close to the aft fuselage. One man placed a sling around the fuselage and to the crane on the Cletrac, and it was winched off the ground. The third man removed the dust cover, cotter pin and nut, removed the tail wheel and replaced it with the serviceable unit in very quick time. The pilot was then signaled to take off, and catch up with the formation. It did not take long for the blowing of tail wheel tires to become a thing of the past.

In the bombardment groups, the aircrews normally consisted of 10 men who depended on a larger ground crew that we had on fighters. There were far more personnel on the bomber bases due to the larger aircrews and support crews. With fewer personnel in the fighter units, all those assigned to a given squadron became better acquainted and this led to many friendships that have continued to this day.

When one served as a mechanic in an Army Air Force unit in a combat area and was involved in a long work hours an resulting fatigue, you were never bored with too much idle time. Being busy kept one’s mind occupied and time passed more rapidly. That’s the way it was and that was the way I preferred it to be.

The ground crews dept. the aircraft available to support the mission, which simply said, was our job.

(End of DeShay narrative)

Rare WWII color photo of flight line.

“Now all the youth of England are on fire, And silken dalliance in the wardrobe lies; Now thrive the armorers, and honour’s thought Reigns solely in the breast of every man.”

So wrote William Shakespeare of the armorers in the Prologue to Act II of “Henry V.” Our armorer, Willard Bierly, also still thrives, and has a vivid memory of many of the incidents of life on a thriving airfield of the 1940. Armorers, even more than mechanics, seem to have been reticent about putting their memories on paper. Bierly’s input gives a unique perspective to the ground crew story:

The flight manual issued in January 1944 by North American for P-51B and C aircraft includes a table of contents listing the 8 categories covered. They are printed on a background of 8 linked machine gun cartridges. What better way to point out that these magnificent flying machines were merely a vehicle to get machine gun fire within a few hundred yards of enemy aircraft.

Certainly our Mustangs made fighter sweeps, flew intelligence missions, did some strafing and a little bombing, but the primary mission was to deny the Luftwaffe access to our heavy bomber formations. The big Browning M2 machine guns fired by proficient pilots did just that, frequently at great heights and at incredible distances from their base.

The mechanics kept the planes in the air; the armorers kept the properly sighted guns working; the radio people kept the pilots informed while in flight, and a myriad of others also supported them on the flight line.

Following a stint at the Army Air Forces basic training center at Kearns, Utah, I was assigned to the school for fighter aircraft armorers at Buckley Field, outside Denver. The base was built expressly for the purpose. Each class of approximately 600 men spent the first week on KP and the following 10 weeks, 6 days a week, studying subjects that, in a peaceful world, would have been illegal. It wasn’t long before we were tearing down and assembling machine guns blindfolded. In England, never once did I need to work on a gun blindfolded, nor did I find application for the theories of magnetism or optics on which we took tons of notes in lectures.

The highlight was the week spent at Lowery Field, near Denver, that had formerly house the only Army Air Force armament school. At Lowery we put the theory of machine gun synchronization into practice. I have often wondered about the disposition of the Boeing P-12s, Consolidated PB2As, and the one Curtiss P-37 on which we actually fired live ammunition through whirling propellers. to complete the course, we had to synchronize the two caliber .30 machine guns on the P-37, with the long, long nose that consequently made it the most difficult to time. As was the routine of most graduates of AAF technical schools, we were destined for either Atlantic City, NJ; Sheppard Field, Texas; or Hammer Field near Fresno, California, to await assignment to fighter groups. I went to Hamilton Field, north of San Francisco.

It was at Hamilton that I was assigned to the then-forming 357th Fighter Group, soon to equip with the Bell P-39 Airacobra. The ensuing training took us to Tonopah, Nevada; to Santa Rosa and Marysville, California; then to Ainsworth, Nebraska, where we left the well-worn P-39s for a short stay at Camp Shanks, an embarkation port in New York, before a less than luxurious ride to Europe on the “Queen Elizabeth.”

Most armorers, while we were at Tonopah with all that wide- open space, managed to “accidentally” shoot a cannon, either the 20mm Hispano-Suiza AN-M2 with its 60-round drum, or the 37mm Browning M4 with its 30-round capacity. I have often wondered how many of these unique cartridges were souvenired. It didn’t take long to discover that the 37mm could be safely disarmed by pulling out the blue inert projectile, dumping the powder, and after pushing the cartridge case into the stand to strike the primer with the point of a nail. Though the projectile was inert in the sense that it contained no explosive charge, it did have a tracer compound that was something you wouldn’t want to have around the house. The procedure was to stick the nose into the sand, place the tip of a caliber .50 ramrod into the tracer compound and strike the ramrod handle sharply with the mallet from every armorer’s kit. This produced a spectacular fireworks display for many seconds. If any of you ancient armorers have a souvenired round with a painted yellow explosive projectile, I suggest a quick trip to a very large body of deep water. The only time I saw a 37mm cartridge with the yellow painted projectiles was at Santa Rosa where we had four planes on alert in the event the Japanese explored the West Coast. For this, the group was awarded the American Defense campaign medal; that is the one with the predominantly blue ribbon, guys!

At Tonopah several of the more adventurous armament men conned the base ordnance people out of a spade grip and, festooned the belts of .30-06 ammo that would have made Pancho Villa envious, wandered into the desert with a Model 1919 Browning to shoot rattlesnakes, rabbits, and large boulders.

There were plenty of machine guns stacked in the armament tent because two of the four wing guns were removed from the Airacobras. This was great sport until someone in another outfit was shooting tracers at night that got people excited and precipitated the order that no more guns were to be taken off base, including our ugly old Model 1917 Enfield rifles.

Two synchronized M2 Browning .50 machine guns were installed in the nose of the P-39s and fired between the propeller blades. If not, they made a hole in the back of the blade and a bulge near the tip. A plane returning to base with an eerie whistling sound meant that some armorer should have paid more attention to the course on synchronization. These two guns could be recharged from the cockpit by pulling on the charging handles, one on either side of the cockpit. The four .30s could also be recharged by pulling the four D handles on the floor, connected to the wing guns by cable. The big nose cannon fired right through the hub of the prop so no synchronization was required.

The group pioneered the use of exotic weapons like all the nuclear testing in Nevada by dropping M38A2 practice bombs. These weighed about 100 pounds, were painted blue, were filled with sand and contained a small spotting charge of black powder so the pilots could see where their bomb fell. These were inexpensively made of welded sheet steel. We also inventoried a small cast iron bomb weighing about three pounds that contained a shotgun shell spotting charge. I haven’t the haziest idea of how, or if, they were used.

While at Santa Rosa, the pilots’ training included shooting at screen-type tow targets pulled with a cable by another P-39. These screens came in two sizes: 4 feet wide by 20 long or 6 by 30. They were made of thread-wrapped fine woven wire so when the screen was pierced by a painted bullet it would leave a colored ring to identify the pilot. Trays, probably cookie sheets, were filled with a slow-drying paint of various colors and the business ends of caliber .30 ammunition were dipped to about a quarter inch. each pilot was assigned a color for each mission. the P-39 tug took off dragging the screen until both were airborne and headed for the Pacific Ocean where the firing was done. At the end of the exercise the screen and cable were dropped over the field. Armorers then tabulated the number of hits scored by color.

A story comes to mind about our tenure at Santa Rose. A very serious minded career officer asked a neophyte armorer how he head-spaced our machine guns. “Oh, I just stick my thumb in there, sir.” The pilot, knowing that in a few months he would have to depend on this man, or someone like him, walked away without saying a word. The correct answer would have been to reply that one used the headspace gauge that was a precision machined gauge, accurate to probably 1/10,000 of an inch. The story had a happy ending, as the armorer who had already learned by experience how to adjust the distance between the bolt face and the shoulder of the chamber went on to become an officer in a Fortune 500 corporation and the pilot became a brigadier general.

The group left its /39s in the Midwest and headed for Europe and P-51s. There were no synchronized guns and no cannon, so that was a relief for all concerned. We were first equipped with the B model Mustang that carried four wing-mounted .50s; that was followed by D models sporting three .50s in each wing. As with the ’39s, the guns were M2 Browning air-cooled weapons. They were a short recoil, reliable, 61-pound engineering marvel that fired at 750-850 rounds per minute. The gun was developed by John M. Browning while with Winchester and refined by him at the Colt factory where production and improvements were made in the 1920s and ’30s. With the huge quantities required for the war, 9 industrial firms produced the gun during WW II. I am sure we had examples from all 9.

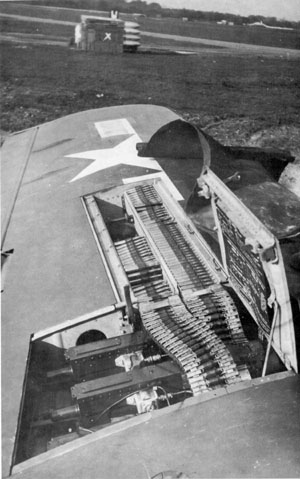

The B model, with two canted .50s in each wing, had a fault not discovered until used in combat. The feed mechanism, designed to lift 35 pounds of ammunition, was not enough to pull the belted ammunition through the articulated ammo tracks during violent maneuvers, resulting in many stoppages. The inboard guns’ ammunition trays each held 350 rounds and the outboard guns each carried belts of only 280 rounds. The fact that the four guns were mounted in a slanted position also contributed to stoppages. Booster motors with star wheels salvaged from Martin B-26 turrets did the trick of providing the extra energy to properly feed the guns. The boosters were so successful that additional quantities were requisitioned to modify all B models.

Although the guns were equipped with electric heaters that were clamped over the coverplates, difficulties were encountered due to the colt until it was discovered that the solenoids used to fire the guns were freezing. A good wrapping with masking tape followed by several coats of shellac solved this problem. The difficulties found in the Bs were not present in the Ds, as the guns were mounted vertically and the feed tracks were more in a straight line. The ammunition first used in combat was the traditional loading of 2 armor piercing (black tipped), 2 incendiary (blue tipped) and one tracer (red tipped) with the pattern repeated throughout the belt.

It was later discovered that this stream of tracers was of as much value to the enemy as our pilots, so the tracers were removed and only used near the end of the belt to warn the pilot that his ammo was almost exhausted. About March or April 1944 the M8 silver-tipped armor-piercing incendiary projectile began to flow through the supply system and was originally only issued to “management”–flight leaders or better because of its scarcity. As above, the tracers were used only near the end of the belt to warn of low ammo.

The D’s ammo trays held 400 rounds for each of the two inboard guns and 270 for the center and outboards. For those statistically inclined, for the first 270 rounds, with all six guns firing, our pilots were feeding the Luftwaffe 154.36 pounds of hot, hard metal at 2,800 feet per second. In the event of a malfunction it was impossible to recharge the guns in flight.

The ground crews, though at nowhere near the risk as the pilots, soon learned that they were engaged in a different kind of war–for keeps. The German aircraft that we knew were overhead in the early days of our stay in England soon convinced us that people could get hurt. The first P-38 and P-47 I saw in late 1943 attested to this. Both had sustained battle damage and emphasized the fact that this war was a two-way street. We dug slit trenches and used them a few times. Our executive officer, who had been in WW I, saw to it that they were long and deep.

The unique British public address system, known as a Tannoy, piped announcements all over the base, including air raid alerts. An “Attention all personnel, air raid warning purple,” indicated enemy air activity in the general area. This was usually followed by the “Air raid warning red” meaning enemy aircraft were in the immediate area. At the same time, sirens could be heard and most often searchlights were probing the sky as any enemy intrusion was usually at night. The longer we stayed in Suffolk County, the more these alerts were ignored as we were never the target of German bombs, and only a visit or two by German aircraft.

I don’t believe there was an air raid alert the night we were strafed and the mess hall sustained minor damage. If there was an alert, my defense will be the statute of limitation on wartime memoirs, as 45 years is a long, long time. There was little direct involvement for the ground crews as we progressed through 1944 until the V-1 flying bomb made an appearance in June. We were never the direct target, only in the flight path of the infernal “buzz bombs.” They would have been a fun diversion if it hadn’t been for the fact that people were getting killed and maimed wherever they fell west of us, as we were close to the North Sea. We also saw the contrails and tiny glow of the flaming propellant pushing the German V2 rockets toward Greater London.

It is a miracle that we did not lose people to accidents. Whirling propellers, gasoline and loaded machine guns are all accidents waiting to happen. We once burned the armament building. Two good things happened: one, nobody was hurt, and secondly, we destroyed the heavy refrigerator that we had to inventory to keep the combat film cool in the event we ended up in the tropics! Probably a dozen men were busy at the long work benches in the building. We were cleaning gun parts with gasoline in pans made by cutting down metal liners from .50 ammo cases. This was SOP. What wasn’t good was when someone spilled gas that found its way to the coke stove in the center of the building. The lazy blue flame that worked it was back to the spilled pan gave us just enough time to evacuate before the building went up in a large ball of fire.

Speaking of stoves, the armament huts all had English issue coke-burning stoves with sides that looked like they had been peened from inside. This was the result of the few .50s that found their way into fatigue pockets after being run through the guns to make sure they were properly charged, or from unloading them. It was no accident when these were dropped into the stoves just to watch the lid pop up or to awaken some sacked-out ground crewman. It was an accident the afternoon when either the tail or ball turret gunner from a returning B-17 decided to clear his guns over our base and those two rounds, as they clattered to the ground, nearly hit this armorer.

Once we were told to bury some condemned ammo so it would not find its way into our aircraft. We had an air-cooled .50 with spade grips for defense purposes mounted on a weapons carrier. We took the ammo over to the North Sea in the back of our truck and proceeded to shoot it up–that was easier and a lot more fun that burying it. Our targets were the unneeded English beach defenses erected to repel the 1940 German invasion that never materialized. These defenses included pillboxes, mines buried in the beach, and the Beatty scaffolding that lined the shores to impede the progress of landing craft. One armorer would stand in the back of the truck to watch the corners disappear from a blockhouse. The occasional explosion of a land mine was a bonus. No one ever questioned this questionable activity!

Mustangs were complicated machines, and even the best crew chiefs occasionally had to “red X” his plane because of some problem that made it unsafe to fly. Usually the mechanic signed off, attesting that the craft was back in service. Rarely did an armorer, who also signed for the condition of the guns, sight, shackles, and camera, have occasion to “red X” as his responsibility was not nearly as great. I “red X’d” a plane only once. That was because the trigger mechanism on the stick wouldn’t energize the solenoids that converted electrical energy to the mechanical force that actually released the guns’ bolts.

I can assure you that an armorer who kept a plane from flying a mission had the immediate attention of the squadron engineering officer. A good, conscientious armorer went to the photo lab to watch his guns being fired in anger. In the early days when tracers were used, one could see if the bullets were properly converging at the range requested by the pilot. The formal way to harmonize the guns and camera was using optical boresighting equipment aimed at targets positioned on a metal stand at a range of 1,000 inches (83.3 feet). A good armorer sent home for nickels that were the same diameter and a lot harder than the fiber discs in the buffer that dampened the rearward thrust of the bolt. the grand idea was to increase the gun’s rate of fire, and that was accomplished because there was a minimum of dampening effect with a harder disc. It was soon realized that although this practice did increase the rate of fire, it was hard on the guns and resulted in malfunctions.

At Buckley we learned a lot about general-purpose bombs, fragmentation bombs, and even incendiary bombs stored in containers not unlike an oil drum that was opened shortly after release. We never used the incendiaries; the frags about once and the big, dumb 500-pound high-explosive jobs only a few times.

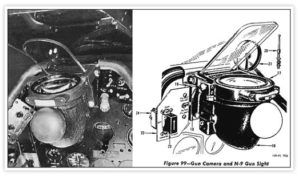

Bombs were fused, both nose and tail fuses after the bombs were hung on the shackles. An arming wire, secured to the shackles, was run through the hole in the fuse from which the tagged safety pin had been removed. The two tagged pins were presented to the pilot. As the bombs fell away from the airplane, the arming wire was pulled from the fuses allowing the arming vanes or propellers to rotate and also fall away after a few hundred feet. At that point the bombs were hot. If memory serves me, we loaded and unloaded about as many bombs as were actually dropped. I don’t recall having used any of the delayed action or booby-trapped fuses we had. I do recall watching some guy driving via back roads from the pub in Yoxford with a keg of beer dangling from the winch on the back of a bomb service truck. the designation of the gunsights we used on the B models were the N-3 series reflector sights. They were essentially a piece of glass set at an angle in front of the pilot, through which was projected a light ring with a dot in the center. The intensity of this light was controlled from a rheostat in the cockpit. All the pilot had to do was place his target in the center of the ring and pull the trigger on the stick. Of course, if it was a deflection shot it was more difficult–a hell of a lot more difficult, as the lead had to be estimated just as in wing shooting at birds with a shotgun. Only these birds were going hundreds of miles per hour, and they shot back. The N-3B also included the Type A-1 reflector head for low-level horizontal bombing. Fighter groups in a strategic air force were not noted for their bombing skills, but the device looked efficient in the posed cockpit photos of our pilots. As far as I know they were never used and were soon removed.

Captain Jim Browning in his P-51B with N-3 Gun Sight

The early P-51Ds were equipped with the N-9 sights that were subsequently replaced with the K-14 computing sight that was truly an engineering marvel. This sight also used light projected onto a glass but the comparison stops there. The combination of gyroscopes and magnetic electrical fields in the box considered the speed of the projectiles, the average speed of the target as well as the usual distance between two aircraft in combat, and fed the information to the images reflected on the glass that moved as conditions changed. In other words, the sight calculated a typical deflection that made the pilot’s hunting much easier. However, the pilot did have to set a knob to correspond with the wingspan of the enemy aircraft and, using a twist grip on the throttle handle, keep the foe centered in the circle of six diamond images and the center dot. I recall cutting into the cowl with a hacksaw to install one of these sights that was larger than the issue N-9. replacement aircraft came with the K-14 as standard equipment. Every armorer spent a week at an English base near Blackpool, attending school on the sight which was an RAF development.

N-9 Gun Sight used before being replaced by the K-14 Gun Sight

K14 Gunsight

This old armorer could be wrong, but would make book that our casualties significantly decreased and those of the Luftwaffe increased about the time the K-14s were installed, which was also about the time the M8 armor-piercing incendiary ammunition was introduced.

The A-N (Army-Navy) gun camera remained throughout the war and could be “fired” without the guns. The guns, however, could not be fired without the camera grinding away. We had an optical device to harmonize the camera with the convergence point of the bullets. The last thing the armorer did just prior to a combat mission was to remove the sticky-back fabric patch from the camera aperture in the leading edge of the wing.

Bomb shackles didn’t present much of a problem and were used on almost all missions to carry the 108-gallon English drop tanks. I believe that the whole group was grounded for a day or two while we awaited a particular part of the shackle that had been found with a defect of some sort.

Just as the war was winding down in Europe we began to receive aircraft equipped with rocket-launching racks. These were removed and I never saw a rocket on our base. the ground crews built “line shacks” primarily with the boxes in which the 108-gallon tanks were shipped. Some had galvanized iron roofs acquired from gosh knows where. Others had floors made from slabs of concrete; most had windows and all had a stove made from a small grease drum or similar container and a stove pipe also acquired from mysterious sources. The ubiquitous ammo can liner, mounted on an exterior wall, was used as a fuel reservoir for the mixture of gasoline and oil fed through tubing salvaged from some derelict aircraft to sizzle and sputter on a brick or two in the bottom of the stove. In my area, each hardstand had a shack built by the crew chief and his assistant for their comfort and to store tools and small expendables. A group of several compatible armorers would build a shack at a location central to the aircraft to which they were assigned. I know of one that contained a double bunk and a chair not unlike a chaise lounge. This “furniture” was custom made from scrap wood and upholstered with sections of thin mattress and bolsters, all tagged with the English broad arrow. From whom we stole these creature comforts will forever remain a mystery. Our line shack was a place to sweat out missions, protected from the weather, but was used on a 24-hour basis for a couple of days on or about June 6, 1944.

When the pilots returned the first thing we watched for was the end of the gun barrels. If the reddish-brown patch was still evident we new the guns had not been fired, but if the muzzles had a dirty, dark gray appearance we could expect a story and hope for an opportunity for the crew chief to paint another swastika on the side of the Mustang. That was the name of the game.

As I write I am looking at an aerial photo of Station 373 that was the formal designation of our base. It was a large field and we soon had well-worn paths along the hedgerow boundaries between the local farmers’ fields. the areas between the three runways and the taxi strip were cultivated. there were few fat GIs. We walked everywhere. Near the end of out stint at Leiston, a shuttle bus was operated throughout the area including a circuit around the entire taxi strip. This was a four-by-four with benches along the sides, a canvas top and metal steps running down the back. At least one of the squadron dogs was a regular commuter.

By and large the chow was good. The “by and large” qualification covers the powdered eggs that somehow were never quite palatable and the all-too-frequent servings of brussels sprouts. Occasionally the usually adequate quartermaster supply line fouled up. We once went for a week or two with brussels sprouts served three times a day. We ate from stainless steel trays retained in the mess hall but were required to carry our own utensils plus that infernal canteen cup that was too big to fit any pocket so the handle was hung over a belt. It was awkward to say the least, uncomfortable to carry and always in the way.

Infrequently the PX ran out of cigarettes, though most of us maintained a reserve supply to fall back on. the heavy smokers resorted to rooting around in the sand buckets used for fire protection and that made an excellent ashtray. Thousands of cigarettes were snuffed out by pushing deep down in a bucket of sand. Our ration card also included candy bars if one considered a Zag Nut to be candy. I think a Zag Nut was made from imitation sugar, artificial chocolate, and a peanut butter substitute. They complemented the Raleigh cigarettes that were the usual fare.

My three years as an armorer is something I will never forget but an experience I wouldn’t want to repeat. Earlier I mentioned a story concerning headspace and will end with one not so funny. On D-Day my pilot, strapped in his cockpit, asked if he could borrow my knife as he had forgotten his. It was a precaution to puncture his dingy should it accidentally inflate in the cockpit. He never returned my knife.

(End of Bierly narrative)

“Without their service, nothing can be achieved. I must say that their endurance, their skill, their patience, although different, is in every way the equal of that of the aircrews.”

To old mechanics, armorers, and other ground crew troops, it is pleasant to read such words, even though these are said to have been uttered by one of the great despots of modern history, Hermann Goering. He was, of course, referring to his Luftwaffe crews, but I suspect the men who toiled to keep the FW-190s and Ju-88s flying had much in common with us on the other side.

One of the popular myths of WW II is that all American youths were mechanically inclined because they had all owned hopped-up hotrods in their high school days. Or course some of them did, but nevertheless the story is largely nonsense. Trying to keep a 10-year-old Model A Ford running for a few years in our late teens did not provide a useful mechanic to a USAAF desperately trying to manage a huge expansion.

When one volunteered for the AAF (July 1942 in my case) he was given three choices of a career, but this was mostly eyewash (or “prop wash”) as the Army was going to put him where they thought he was needed anyhow. Cadet training and aerial gunner were not possible in my cas due to below standard vision, so it was ordained that I was to be an airplane mechanic.

In late October and early November 1943 all three squadrons of the 357th FG underwent a thorough pre-overseas inspection. My squadron was at Pocatello, Idaho, having survived the inspection. The three squadrons met again at Camp Shanks, NY, ready to proceed to some unknown theater of operations.

One of the world’s great luxury liners, the RMS “Queen Elizabeth,” provided the sea transport for the 357th and some 14,000 other troops. After five days at sea, the 30th of November found our great ship in the harbor at the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. Debarking was a lengthy process, about which I recall nothing, and after a long night train ride the 357th found itself at a base called Raydon Wood, assigned to the 9th Air Force.

Raydon was like dozens of other bases sprouting out of the East Anglian soil, and a muddy soil it was in the English winter. Everything was new to us–the weather, the Brits, the blackout, the equipment, the job at hand, and the upcoming mission. I do not know when we learned that we were to operate the P-51, but they began arriving soon after we did. None were new aircraft, most hand-downs from the 354th Group, the first to take the Merlin Mustang into combat (we were the second). I recall a few machines which had RAF roundels visible under the OD paint. The group aircraft status reports show that, by new year’s day, there were P-51Bs on hand plus an Airspeed Oxford which we kept for a few months. During January the buildup to the 75 aircraft authorized proceeded rapidly.

Apparently a few maintenance men were hurriedly sent to school on the P-51, but it was much later that I attended a course on the Merlin engine at the Blackpool depot. In retrospect, the men who were to keep ’em flying were grossly undertrained by current standards. In later years, it was (and is) standard practice to have a field training detachment on station when new aircraft arrive. We had no such unit and learned as we did the job. Undoubtedly this approach cost us aircraft and a few pilots over the next 16 months.

Immediately upon arrival of the first few P-51s, the pilots began an intensive checkout and learned much–by doing. The P-51 in those days was never started on its internal battery, but always with a battery cart, all supplied by the RAF. Huge unwieldy carts with giant iron wheels, they contained a battery pack and a small gasoline engine and generator to keep the batteries charged.

During the start, the airplane’s battery switch was left off and turned on after the cart was disconnected. I recall one incident when, after startup, the pilot motioned me onto the wing and pointed out that none of the instruments were indicating. Luckily a flash of intuition came to me, and flipping on the battery switch restored the instruments to their vibrant selves. As I said, we learned as we went along.

We spent Christmas at Raydon, with the new Red Cross Club doing what it could to provide cheer. As 1943 came to an end, it had become obvious to the 8th Air Force that they must have the P-51 if its heavy bomber offensive was to continue and succeed. The groups with the P-47s and a few P-38s were doing the best they could, but their limited range and technical problems precluded any real success on the escort mission. So it was that someone at 8th Air Force headquarters struck a deal with our parent, the 9th Air Force. “Well swap a Jug outfit for your 357th P-51 group.” It was done and in early January the 358th Fighter Group took over Raydon and we moved to their old base at Leiston Airfield, and the 8th Air Force. On 11 February we flew the first combat mission. There would be more than 300 more by the end of April 1945.

During this period we received and operated four different models of the Merlin Mustang, though from a practical point of view there were only two. In addition to the basic P-51B we had a few C models, identical to the B except built in North American’s Texas plant.

Sometime in the spring or early summer of 1944 we began receiving the D model, improved in two major ways. First it had a much superior armament layout, and it had the clear all-round vision canopy. Later in 1944 we obtained a few K models, the same machine as the D except for an Aeroproducts propeller in place of the Hamilton Hydromatic. All P-51s flying in the 1980s have propeller blades without cuffs, but during WW II if the prop had no cuffs the airplane was a K model.

Even with its faults, and it had a few, the Mustang is generally conceded to be the aircraft largely responsible for defeating the Luftwaffe. Possibly the P-51’s most serious fault was that under some conditions its wings were structurally weak. We lost several aircraft and pilots to wing failure, but these were not maintenance related. Maintenance-wise, the P-51 was the star of the trio of US fighters in Europe, being much easier to maintain. the P-38 suffered from numerous design flaws which were not worked out until the later L models arrived near the end of the war. It was also a real maintenance hog, with by far the worst ratio of maintenance to flight hours.

The P-47 was much better, and with a more reliable powerplant, but its turbo supercharger added to maintenance woes The hot section, control system, and ducting on turbos were often a source of trouble. Of course, the P-51 had a liquid cooling system the Jug did not, so maybe they evened out from the maintenance point of view. A few years later I was crew chief on P-47s for a couple of years, and I prefer the P-51.

All four of the P-51 types, the B, C, D and K, were powered by the Damn Great Merlin, in US service the V-1650-7. A few of the early B models had the dash 3 engine, but those from B-15 and C-5 on had the -7. The heart of the Merlin’s high altitude performance was its superb two-speed, two-stage internal supercharger. Far from being a simple device, the internal aircraft engine supercharger required very intensive development in the 1920s and ’30s. Rolls-Royce, realizing its importance, devoted a vast amount of effort in the field. From 1940 onward, the effort paid off. the V-1650-3 and-7 were identical except for the supercharger. the aneroid pressure switch on the dash 7 was adjusted to shift to high blower at approximately 14,500 feet, about 5,000 feet lower than the dash 3. Gear ratios were also altered. Dash 7 ratios were lowered, resulting in the impellers turning slightly slower. High blower ratios were slightly over 8:1 in the dash 3, approximately 7.4:1 in the dash 7. Critical altitude at which max horsepower was obtained under given conditions was lowered from 29,000 to 23,000-plus. Reasons for this change are unknown to me, but it did result in a lowered performance at high altitude, which most pilots did not like. None of this, of course, posed any problems for the mechanics, except possibly the aneroid switch, and in fact we did not know or care what blower ratios were as there was nothing we could do about them.

Although they are often called Rolls-Royce Merlins, none of the production P-51s had R-R engines. All were license-built by the Packard Motor Car Company, once a builder of fine cars, but now long gone from the automotive scene. There were minor differences between R-R and Packard units, but the U.S. engines retained the Whitworth standard threads of the British version. these required special wrenches and wide usage of the old reliable crescent wrench. According to the P-51B manual, when delivered to the AAF each aircraft had stowed in its ammo or gun bays: 1 kit engine tools and 2 set prop tools; 1 kit armorer’s tool rolle; engine and cockpit covers, and sway braces for the bomb racks; 1 kit NAA special tools; technical orders and instruction books.

How much of this remained when we got them from the depot I do not recall. The listing of the tech orders brings up another point. In later years the military services began stressing to mechanics the absolute necessity of using the technical orders when doing maintenance work. My memory tells me that we did not use them as much as we should have. The TO library was maintained in the engineering office, a mile or more from most hardstands, which tended to discourage their use by line mechanics. I’m sure we lost aircraft because of this. Every aircraft crew should have had them readily available but I do not recall that they were.

There were, of course, a shocking number of non-combat losses in the 8th and every major air force. These stemmed from the same causes we have today–design flaws, material failure, pilot abuse and error, weather, maintenance error, and often a combination of them. Losses were often impossible to attribute to any one cause. Even though maintenance error was a part of life, I am convinced that all the mechanics I knew were a dedicated lot who did their best to provide safe, serviceable aircraft to support the mission. I do not have any figures, but former highly-placed group officers have told me that the 357th had one of the highest operational readiness rates in Air Force history.

Our highest level of maintenance was the resident service squadron (the 469th in our case). Not part of the group, it was nevertheless part of the family and provided heavy maintenance support the squadrons could not do. Each squadron had a hangar crew, or actually two, as they worked round the clock in two shifts, doing engine changes, radiators, control surfaces, battle damage repair, etc. Last were the flight line crews, normally three men each–crew chief, assistant crew chief, and armorer. Though I was a crew chief later, most of the operational period I was assistance crew chief with Ray Morrison and we went through several P-51s, all coded G4-P. We had two different armorers, the first remembered only as “Whitey,” and Corporal Harry Bailey who stayed with us until the end.

The squadron Charge of Quarters (CQ) was the man who jarred the day into motion for the flight line mechanics. He was the duty NCO who manned the squadron orderly room at night, and the first to receive information on the day’s mission. At the appropriate time, he made his rounds awakening the pilots, mechanics and others who would be involved. The time depended entirely on what time the pilots’ briefing was set. After flipping on the lights, the CQ almost always said the same thing: “Briefing at 0700, max effort, max range.” The only variation was the briefing time. The flight line crews then knew all they needed to know.

Bicycles, jeeps, trucks, and GI shoes provided the transport to the mess hall, thence to each crew’s individual hardstand. usually both crew members, C/C and Assistant C/C were on hand, but if one were off or on other duty, the other handled the preflight. Cockpit and wing covers and the pitot tube cover were removed first, and the prop pulled through a few turns, then the preflight inspection began. Compared to today’s military aircraft, the P-51 was remarkably unsophisticated. Nevertheless, the preflight inspection as laid in the manual was quite lengthy.

Mostly it consisted of visual inspections, many of which had been completed the previous day. All reservoirs were checked for fluid level, and included the two coolant systems (engine and supercharger aftercooler), hydraulics, battery, engine oil, and fuel. An inspection was always made under the airplane for coolant leaks which often occurred after a temperature change. Incidentally, it was often difficult to tell coolant from water, so we put a fingertip in the puddle and touched it to the tongue. Coolant had a bitter taste and was poisonous if consumed! The method was foolproof, if unpleasant.

If all visual and servicing checks were satisfactory, the engine run was done, using the battery cart to save the internal battery. Because the seat was rather deep to accommodate the pilot’s dinghy pack, we usually put a cushion in the seat in order to reach the brakes and provide better vision. Brakes were set and we usually fastened the seatbelt around the stick to provide up elevators during power check. Flaps were left down, fuel selector to either main tank, throttle cracked open and mixture control to idle cutoff. After yelling “Clear,” the starter switch was engaged (the P-51 had a direct drive starter) with engine prime.

As soon as the cylinders began to fire, mixture control was moved to “Run.” (All 8th AF P-51s had their carburetors modified to remove the Auto Lean, Auto Rich, and Full Rich mixture positions, which were replaced by one notch, Run. If pilots had been free to choose the fuel mixture, it would have been impossible to plan mission times with any accuracy, and many running on rich mixture would not have made it home.) Propeller was already at Full Increase, and throttle was set at 1,300 rpm for warmup.

After engine oil and coolant temperatures were in the green, the engine was run to 2,300 rpm and magnetos checked. With each mag off, the maximum allowable drop was 100 rpm. Propeller governor was also checked: 3,000 rpm were maximum but only for takeoff, not on the ground runup. It was in the area of ignition systems that the Merlin gave much of its trouble–rough engines during mag check were common, also during flight. At least one source of this problem was the highly leaded fuel used, especially for a period late in the war. Sometimes plugs could be burned off with high power settings, and the engine would smooth out. If not, it called for a plug change. It was a common writeup after flight. We must have changed thousands of plugs. British plugs gave the best service, but even with them we seldom got more than 15 or 20 hours out of a set. The exhaust plugs were no problem but the intakes were difficult to get to, especially on a hot engine. Due to burned hands, many were dropped between the intake manifolds where they were difficult or impossible to get out.

After the engine was shut down and everything checked okay, it was mostly a matter of waiting. Fuel and oil trucks were usually cruising on the taxiway, and all tanks were topped off. Windshield, canopy and rear-view mirror were polished for the tenth time or so. The armament man had long since arrived and charged his guns, so all aircraft on the field had “hot” guns before takeoff.

Pilots usually arrived 15-20 minutes before engine start time, via overloaded jeep or weapons carrier. After the pilot was strapped in, his goggles and windshield were given a final polish as start engine time came and some 60 Merlins coughed to life around the airfield hardstands. Then chocks out, and with a wave to the crew, each aircraft took its proper place on the next taxi strip in a snakelike procession toward the active runway. The ground crews, and everyone else on the field, usually sought a vantage point to watch the takeoff–always an exciting event, the sound and sight of 65 or so overloaded Mustangs getting airborne remains a vivid memory.

Mostly responsible for the heavily loaded condition of the aircraft were the two long-range drop tanks. “For want of a horseshoe nail,” the old saying goes, “the battle was lost.” Almost as humble as the nail was the droppable fuel tank, so vital to the success of U.S. fighters in Europe. The tanks we used were the paper composition units of 108 U.S. gallon capacity built in huge quantities by British companies. They were installed on the racks for the next day’s mission the night before and filled at that time. During operation they were pressurized to ensure positive feeding at altitude by the exhaust side of the engine-driven vacuum pump. The piping and fuel flow had glass elbows which would break away cleanly when the tanks were dropped. Even though they were pressurized, it was necessary to coax the fuel into the system during preflight. After switching to drop tank position, the engine would tend to die, and the selector was quickly put back to main, then back to drop tanks until they would feed properly. On the mission they were dropped when empty, or earlier if combat demanded it. With 15 groups operating, 8th Air Force fighters required almost 1,800 tanks a day.

With all tanks serviced, 485 gallons, there were almost 3,000 pounds of fuel aboard. With the weight of the guns, ammo, and other operational equipment the P-51 was heavy! The handling characteristics would come as quite a shock to a 1980s Mustang owner if he were to fly a fully loaded airplane. Sometimes it came as quite a shock to 1944 pilots also!

During midday while the mission was out, the line crews were in a state of suspended animation. It was mostly free time to attend to laundry, to read the squadron bulletin board, and to check if your name came up on any unwanted but unavoidable extra duty rosters. There was also time to check in at the small PX for a candy bar, and to take in noon chow at the big consolidated mess hall in the base communal area.

The average mission was 4 to 5 hours, and by the estimated time of return (ETR), everyone was back on their hardstand. If the group came into sight in formation and to the rising snarl of many Merlins, it was probably that there had been no combat. If they straggled in by small groups or individually, it was certain there had been some action. Missing red tape and smoky gun muzzles were final confirmation.

After the pilot had departed for debriefing, the crew had considerable work to complete the post-flight inspection and repair any discrepancies the pilot reported. If you were lucky the airplane was put to bed in time to make it to evening chow.

Most of the pilots and crews developed a close relationship, but like all human affairs, some did not. Many years later some of the pilots told me that they regretted not getting to know their crews, but that they were just too engrossed in their own thoughts, and many readily admit that before a mission they were very apprehensive or even fearful. Considering that the skies of Europe in 1944 were very dangerous, this is an entirely understandable emotion! It is to their great credit that all but a few pressed on regardless, flew their missions and fought the war the best they could. On the other hand, a small percentage of fighter pilots appeared to be without fear, and looked forward to the excitement and challenge of air combat. In recent years, several well- known fighter aces have told me that they enjoyed their combat tours–an attitude entirely incomprehensible to my ex-bomber friends!

The air war against Germany was costly in lives and aircraft; 8th Air Force alone lost almost 30,000 dead. The 357th Group lost about 150 P-51s on operational missions, but about half the pilots became POWs or evaded capture (about a dozen) and returned after the war. As near as can be determined, 82 men of the 357th Group lost their lives in the line of duty. This includes many lost to accidents in the ZI and in Europe. Of course, when a crew lost an aircraft and pilot, it was a depressing time but we seldom knew, except in a general way, what had happened. My crew lost two pilots. One of these, Lt. Otto Jenkins (a double ace) bellied in behind Allied lines and returned, only to die five months later in a fiery crash on home base. The other, not our regular pilot, lost his life when 44-14245 crashed not far from base in what was probably a weather related incident.

Even though much has gone from the memory after 45 years, a kaleidoscope of incidents remain: a taxiing P-51 whose pilot used too much power and rode the brakes–until the heat burst the hydraulics and both wheels caught fire. It was quite a sight until the tires burst and the Mustang came to a halt. Leiston Airfield, F-373, was the closest to the North Sea and a frequent refuge for cripples–a B-24 with its nose turret blown off; a B-17 with a bloody boot sitting in the hatch; a Lancaster on its belly; a P-47 with a wounded pilot who asked for assistance out of the cockpit. Another P-47 with battle damage that caught fire after landing had shorted out the gun circuits which then fired the remaining ammunition. the P-38 pilot who tried to slow roll on takeoff and went in upside down just outside the perimeter.

Then there was the great Luftwaffe raid on Leiston, or maybe two of them. Even though many men have given me their recollections of what happened near midnight on 6-7 June 1944, there is little agreement except that a single e/a saw a glimmer of light from the mess hall, serving midnight chow, and put a burst of cannon shells into that citadel of culinary delight. Other than a few holes in the roof and the utter confusion of overturned tables and good, there was no significant damage and our base defense .50s managed to knock off a few minor pieces of the intruder.

As invited “guests” on foreign soil, many of us tried to see as much of the country as duty allowed. Some, of course, limited themselves to the local pubs and the local girls. I managed a few passes to local towns and several trips to London, which ignited a love for that great city that endures to this day.

There were two missions on the 25th of April 1945, one a full-strength but uneventful escort to Hallein. Late in the evening, Lt. Ed Hyman led four Mustangs as escort for a Catalina and a Warwick searching for some missing airman down at sea. Wreckage and a dinghy were found but no sign of life, and four hours later the four P-51s returned to base. Ed Hyman, with Ray Morrison and myself, and our armorer, Harry Bailey, were the “owners” of P-51D 44-72489, and when the wheels touched down, 489 made the last wartime landing of the 357th Fighter Group.

By midyear the group was in Germany on occupation duty, but for most of us it was a short but interesting interlude before we returned to the Zone of Interior and to a different world–and a new and different life.

(End of Merle Olmsted narative.)