See Them Tumbling Down

Advanced Fighter Training in Bell’s P-39 Airacobra – After Pilots Mastered It, They Were Ready for Anything! By Merle C. Olmsted

Aesthetically, Bell Aircraft Corporation’s P-39 was a triumph. In appearance it was thoroughly modern – sleek, lean and mean, with a big cannon and sundry other guns, all sitting on a neat tricycle landing gear. True, it was a bit odd, with the engine installation amidships, but this is said to have been the result of Bell engineers’ desire to mount the 37mm cannon in the most effective way.

Sadly enough, the Airacobra never lived up to its aesthetic attributes for several complicated reasons. The old aviation saying that, “If it looked right, it was,” was once again proven to be just a saying. Come to think of it, the big Oldsmobile cannon never lived up to the hopes held for it, either.

Origins Of A Fighter Group

Looking back from the 1990s, the mind-numbing statistics and complicated logistics of the 1940s seem astounding. Despite all the confusion, false starts and undoubted massive errors resulting from the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, which caught it unprepared and plunged the country into all-out war, the United States accomplished a long list of miracles. It is unlikely we could do it again, in a different world and a different country, 50 plus years later.

Nine days after the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Headquarters, 4th Air Force, San Francisco issued General Order #47. It was titled, Constitution and Activation of Certain Army Air Force Units, and had an effective date of 1 December, 1942.

The certain AAF units were Headquarters, 357th Fighter Group and its component squadrons, the 362nd, 363rd and 364th. The order further called for a cadre of personnel to come from the 328th Fighter Group at Hamilton Field, near Vallejo, California, and allowed four months for the new group to be at 100 percent strength.

As 1942 ran down to the holidays, small groups and individuals mostly rookies out of various training schools, began to drift into Hamilton and were shuttled away from the lovely prewar base, down to the mud flats with tar paper-covered barracks. There was little knowledge, equipment or supplies, but these slowly became available.

Commander of the new group was to be Lt. Col. Loring Stetson, Jr. who was to get his unit off and running before leaving for a combat command six months later. Two of the three squadron commanders, Captains Hubert Egnes and Varian K. White, were combat veterans of the early Pacific fighting and both held the Silver Star. Captain Stuart Lauler was to lead the 363rd Sqdn.

Most of the enlisted men of all specialties were assigned from the 4th Air Force Replacement Center at Hammer Field, Fresno, Calif. During the brief period at Hamilton, the only busy people were the administrative types whose job it was to get the unit operating, sort out the people and make everything legal in the Army manner. On 4 March, 1943, with no airplanes, but most of its ground staff assigned, movement began by rail over the Sierras to Central Nevada and the Tonopah Army Airfield Bombing and Gunnery Range.

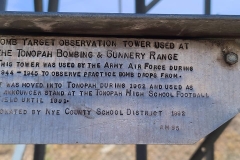

Tonopah was a silver mining center at the turn of the century and is located midway in the remote desert between the gambling meccas of Reno and Las Vegas. In 1943, it was a desolate watering hole and road stop of about 1,500 people, its silver mines played out. To the good fortune of the town, the War Department had decided it was ideal for a training base. Consisting of about 3,000,000 acres, it was huge and had been in operation only a short time before the 357th arrived in March, 1943. In many ways Tonopah was an ideal location for bombing and gunnery. Due to its isolation, there were few people to complain about noise and low-flying aircraft. However, whoever picked it for P-39 training could not have been very familiar with that airplane’s flight characteristics. The elevation of 5,426 feet was nearly half of the P-39’s useful altitude. In the summer, with temperatures over 100 degrees, density altitude would be about 9,500 feet, requiring extremely long take off runs. Fifty miles to the North were 12,000-foot mountains, and 90 miles to the West the peaks rose to over 14,000 feet. A few months after the 357th departed, in mid-summer, P-39 transitions training was replaced by similar training for B-24 crews.

The P-39s which greeted the pilots and mechanics upon their arrival on the flight line were much-used D models, which first appeared in 1941 but were still considered adequate for initial training. The Group slowly began building its pilot strength with recent graduates from Luke Field, Arizona, but the experience level among the enlisted men in the maintenance sections was dismally low. Each squadron had only 3 or 4 old-time NCOs to fill the flight chief and line chief slots. All others were freshly graduated from various specialty schools.

The pilot situation was somewhat better, as each squadron had a Pacific theater combat veteran as commander. The flight leaders, who would be largely responsible for training the newly arrived 2nd Lieutenants, came mostly from the 328th at Hamilton. None of them were high-timers, but at least they had been flying the P-39 for a few months and were probably considered crusty veterans by the new fledglings.

The mission at Tonopah was to raise the unit’s experience level as much as possible in the short time available. A great deal of both day and night flying was accomplished, along with cross-countries, gunnery, formation flying and general rat racing. All of this resulted in a heavy load on the maintenance sections, thereby raising their experience level.

Before, during and after the 357th stint at Tonopah, there was another P-39 equipped unit in residence. This was the 444th Fighter Squadron, whose mission was to transition newly graduated pilots into the Airacobra. Many, but not all, of the 357th pilots went through the 444th course before reporting to the 357th. 2nd Lt, Carroll Anderson trained with the 444th in the summer of 1943. He was not to be a member of the 357th, but we present his classic description of his first P-39 engine start as one that all P-39 pilots can relate to:

“Where’s the starter?! That’s right, it’s on the floor, it’s a heel-and-toe job. The energizer begins its long buildup whine. I tip my foot to engage the starter – and all hell breaks loose! A tremendous crash, followed by a loud clattering noise explodes behind me, accompanied by a corkscrew vibration which wracks the entire fuselage. The airplane feels as if it is coming apart. As I jam the mixture control forward, the nose of the aircraft drops and wobbles. I don’t know if this is because the mixture control, or if it is a natural phenomenon. I sneak a look at the crew chief. He is standing well away from the airplane now, but observing it with wary caution. He isn’t running away, so at least I know it isn’t on fire and what I am experiencing is normal, although the fillings in my teeth are beginning to loosen. With a steady flow of fuel pouring into the Allison engine behind me, the plane jumps and jerks somewhat less, but the racket is still terrifying.” The reader will be glad to know that Anderson’s first flight in the beast went well, and upon returning to the ground he was able to assume the nonchalance of an accomplished fighter pilot. He went on to fly a combat tour in the Pacific in the P-38.

2nd Lt. Tom Beemer, who would join the 362nd Squadron later, was also a graduate of the 444th and has provided not only his input but a rare copy of the 444th Transition Training Manual P-39, We quote some interesting passages from the manual, plus Beemer’s comments:

“The P-39 is very heavy and has a definite settling and squashing tendency, It is even possible, with full gun, to make the ship settle 6,000 feet per minute. Consequently, the glide for landing should never be less than 120 mph, with full flaps. Gradually break the glide of about 200 feet altitude and make a normal landing. Keep stick back, until nose wheel drops. Unless landings are made this way, it is almost impossible to land on a normal field with flaps up, as the airplane is so streamlined that brakes alone are insufficient to slow it down.”

“Do not attempt to impress your earthbound brothers with steep turns and maximum rates of climb close to the ground. Keep a good margin of speed to save you in case of engine failure. This advice applies to all aircraft, of course, but it is particularly true with the P-39s high-wing loading. Rough handling of the controls will result in a stall at any altitude, at any speed, in any attitude of flight in the P-39, particularly in a turn or violent maneuvers.”

“Do not snap roll the P-39. (Advise of the manufacturer’s field rep.)”

The 444th’s manual ends with the usual admonition about buzzing: “Acrobatics at low altitude, low flying and violation of flying regulations have cost many lives, property damage and seriously retarded the training program. Exhibitionism in any from will not be tolerated.”

Good advice, but widely ignored by young pilots! It should be remembered that this manual was written for raw recruits with no experience to high performance airplanes and that many of the things cautioned against could be done with ease by high-time pilots.

Tom Beemer remembers: “This manual was the first step in putting my new silver wings to work – learning to fly the P-39. Reading it in recent years brings several reactions; one is that the ‘39’ was a dangerous little bird. Spin characteristics and prop malfunctions make for scary reading also. Thinking back, though, the ship was far more forgiving than reported here. My second day at Hayward, Joe Broadhead, 362nd Sqdn. Operations Officer, took me up to check me out, suddenly he turned to get on my tail. We ended up nearly stalling in a left-hand turn circle. That introduction to pressing the limits was mild compared to what the rest of us did while Broadhead and Egnes (362nd Sqdn. Commander) were tending to their paperwork. Maybe we were both lucky, maybe the P-39 was better than reported. Maybe both.”

Shortly after the 357th became operational in February, 1944, Beemer had the misfortune to be shot down by a B-17 gunner. Badly injured in a low altitude bail out, he became a POW.

It was inevitable, of course, that pilots were going to die. Training is often as dangerous as combat. Official records from the period are sparse, but we know of at least four men killed during the three months at Tonopah. 2nd Lieutenant Rudolf Bisterfeldt was the first. He dropped out of formation and bored into the desert floor; reasons unknown. Two weeks after his arrival in the desert, after an engine failure on an AT-6, pilot Dave Perron landed on a highway and struck an automobile, demolishing the airplane and killing Lt. Ralph Sullivan, the 362nd’s flight surgeon.

Bataan veteran and 363rd Sqdn. C.O., Captain Varian White, was killed in a night takeoff from Van Nuys, Calif. and lastly, Lt. Bryce Van Cott died in a collision with the future ace, Glendon Davis, who bailed out.

Colonel C.E. “Bud” Anderson, USAF (Ret.) was a newly minted 2nd Lieutenant in September, 1942, reporting in to the 328th Fighter Group at Hamilton for transition into the P-39. Five months later he was a P-39 old-timer and in March, 1943, he, along with Lts. Lloyd Hubbard, Bill O’Brien, Paul Devries and Ed Hiro, transferred to Tonopah to become flight leaders in the new 363rd Sqdn. Nearly two years later, he ended his combat tour with the 357th having scored 16.25 air victories (the ¼ victory was the result of all members of his flight sharing in the destruction of an Heinkel 111 which was unlucky enough to be caught out in daylight). Hubbard, one of the most talented pilots in the squadron, would die in a burst of flak even before the Group became operational. O’Brien and Hiro would both become aces, the later dying in combat during the Arnhem paratroop drop in September, 1944. In his book, To Fly and Fight, Anderson describes the training program: “Tonopah, with its sprawling gunnery range, was where we polished out shooting and bombing skills. Because the place was so remote, we flew where we wanted, often right on the deck, in between the cacti, hugging the sandy gray hills. It was good to know how. Someday, in combat, knowing how to hug the hills could be everything.”

Harvey Mace was another 444th graduate: “I was standing in front of the pilot’s shack one day, when I noticed a P-39 on a long bomber type approach. It was the kind of approach made by less experienced pilots. A hotshot in another P-39 dove down in front of him and peeled up in the usual 360 degree overhead pattern made by more experienced pilots. He was almost around the full circle, when he became aware that he was cutting in front of the other P-39. He gave what appeared to be an irritated jerk on the stick to peel out of the way. The P-39 does not take kindly to this type of treatment and it snapped into a one turn spin, creating a large crater in the desert floor.”

When it was time to leave Tonopah, Mace says, “I was much at home in the cockpit of the P-39. I was learning to love the little beast, in spite of its short fuse.”

During the desert sojourn, the mechanics, too, worked hard to elevate their minimal skills, sometimes 24 hours straight, with only time to eat, attempting to keep the weary D models in commission. Sgt Joe DeShay, who would eventually serve as flight chief and hangar chief in the 364th Squadron, notes in his diary for 18 May: “Worked til 5 o’clock in the morning last night. Dead tired. No mail since Sunday, sure feel lost.”

The author, as a flight line mechanic in the 362nd Squadron recalls working for more than 24 hours nonstop, trying to plug the leaks in those dreadful little fuel cells in the wings.

The town of Tonopah was the only place within many miles for off-duty shenanigans, and its night life was part of the training saga. The bar at the Mizpah Hotel, opened in 1907, was a popular gathering spot, but the Tonopah Club, the major drinking and gambling establishment, was the center for social life for soldiers out on the town.

Then there was Taxscine’s establishment, for those seeking female company. Taxscine died in the mid-1950s and was eulogized in an article entitled, “The End of An Era,” in the local paper. The Tonopah Club burned many years ago, but the Mizpah Hotel is still in business.

Bud Anderson sums up the Tonopah ear: “Here, the pilots of the 357th, having learned to fly, more or less, were taught to fight.” The ground crews, too, had learned their jobs, more of less.

The Groups’ safety record, with four men killed in aircraft accidents, was probably about average for the war years. From June through October, when the squadrons were split up and operating out of various California bases, before moving east into Idaho, Wyoming and Nebraska, the flying safety record was appalling! The following list has been complied in as few words as possible. Since official records are very sparse, it is almost surely incomplete, but some of the events listed will be dealt with in more detail,

Events, Incidents and Accidents

Tonopah, Nevada – 3 March through 2 June, 1943:

1. Date unknown, 2 Lt. Rudolf Bisterfeldt, dropped out of the formation, straight into the desert floor. Thought to be the first casualty.

2. 27 March: Lt Davis Perron, pilot; Captain Ralph Sullivan Flight Surgeon. Engine failure on AT-6. Sullivan killed.

3. Lt. Norman Baxter. 364th Sqdn. Landed P-39 on fire, overran runway end, nose wheel collapsed, tail melted off. Baxter jumped out and escaped.

4. 362nd Sqdn. Listed three crashes in April, no details.

5. Date unknown, pilot Donald Steger, killed in crash.

6. 18 May: Captain Varian K. White killed in P-39 crash, North Hollywood, Calif. (Van Nuys Airport)

7. 23 May: Lt. Bryce Van Cott, killed in crash, collision with G.V. Davis, who bailed out.

8. During June, 60 pilots were assigned direct from training at Luke Field. 2 June 1943: Squadrons moved to Hayward (362nd), Santa Rosa 363rd, 364th and Hdqtrs; in mid-July, 363rd to Oroville, 364th to Marysville, Calif.

9. 10 June: Lt. Virgil Wyss, spun in, bailed out at 400 ft., killed.

10. 11 June: Gail Palmer, killed in crash.

11. 23 June: Gear up landing. 364’s No. 73.

12. 24 June: AT-6 taxied into tree.

13. 25 June: Landing gear collapse.

14. 26 June: AT-6 wing failure. Lts. Joe Oshborn/Saxton Fenemore, killed.

15. 28 June: Bail out, Lt William Overstreet, from flat spin.

16. 3 July: P-39 struck tree.

17. 4 July: P-39 crashed into Clear Lake.

18. 6 July: Lt Hal Plummer, spun into bay, killed.

19. 7 July: Lt Lyle Mather/Clay Davis, collided in air gunnery pattern, both killed.

20. 8 July: A bail out and gear up landing.

21. 9 July: Lt. Gilbert O’Brien, shot off tow target, collided with it and bailed out.

22. 10 July: Gear collapse on takeoff.

23. 11 July: Gear up landing.

24. 15 July: Pilot bailed out of burning P-39. Sgt Joe DeShary diary says: “Saw P-39 fall from 8,000 feet, pilot jumped. Plane fell directly over our area and burned. Cowling fell like leaves.”

25. 14 July: Landing gear collapse.

26. 4 August: Belly landing, pilot confused on gear operation.

27. 6 August: Lt. Bowers, crackup on landing, minor injuries.

28. 10 August: Lt. Roberson, nose wheel collapse on taxiing.

29. 23 August: Lt. Harold Mickelson, hit hill on night landing, killed.

30. 18 September: Lt Donald Soens, crashed from inverted spin, killed.

31. 6 October: Richard Peterson lands in Mexico, hit boxcar.

32. 16 October: F.O. Chuck Yeager bellied in, gear would not come down.

33. 17 October: Col. Chickering/Lt. Currie collided during a gunnery pass at a B-24; Currie landed, Chickering bailed.

34. 21 October: F.O. Chuck Yeager bailed, fire in the air.

35. 9 November: All units entrained for Port of Embarkation (POE), New York

THE INFAMOUS COBRA TUMBLE

“Don’t Give Me A P-39

With An Engine That’s Mounted Behind

It’ll Tumble And Roll

And Dig A Big Hole

Don’t Give Me A P-39”

At this point in our story of the 357th and the P-39 we will address the controversial subject of the P-39 “tumble.” The phenomenon is pertinent to this tale, as it almost surely killed a few 357th pilots, and happened to, or was observed by others. Anyone who was associated with the aircraft, or has followed its history is aware of the unpleasant characteristics. There is, however, little agreement on exactly what the tumble was. Some say it never happened. Others say if it didn’t, something weird did. Then there are those who lived through it, and many others who witnessed this occurrence. Some of these seem to have been a pure tumble – tail over nose, rolling on the wing axis. Others were not so straight forward. All seem to have begun with some sort of high-speed stall, or an inverted stall, followed by violent snap rolls, with or without a tumble, often ending in an inverted flat spin. Whatever the exact sequence, it was a series of wild gyrations, with control stick and rudder pedals being thrashed and stomped about the cockpit. From the resulting spin a normal recovery could sometimes be made, assuming pilot and aircraft had not run out of sky.

Published reports by pilots of the 31st Fighter Group, one of the first units to get this P-39 in 1941, are all similar, but do not appear to follow an exact pattern. The same is true of the 357th pilots who encountered or witnessed the wild gyrations.

Lt. Col. Loring Stetson, who left the Group in July to command the P-40 equipped 33rd Fighter Group in the Mediterranean, wrote back to the Group in October, commenting on the P-39’s quirks. “Our ships aren’t the newest, but at least they don’t tumble and they get the job done.”

362nd Squadron’s Harvey Mace’s encounter with his version of the tumble provides us with a humorous look, as told in his book, The Highs And Lows Of Flying. As Mace tells it, someone in Group Headquarters decided it would be good practice for all three squadrons to meet in one big rat race dogfight over the San Francisco Bay area: “We had the big melee going and I was hot on the tail of an opponent when he pulled up in a loop. At the top of the loop, I happened to look to my left, just in time to see some poor soul fall into a tumble. I was so distracted laughing, that I let my own airspeed fall too low and the P-39 promptly reminded me of my foolishness by snapping into a immediate tumble of my own. The stick jerked out of my hands and all I could do was keep my hands and knees out of the way of the flailing stick until the airplane decided to do something I could recognize. Finally, the ship stopped tumbling and settled down absolutely straight and level – but with no airspeed on the dial. I very carefully took hold of the now quiet stick by two fingers and gently pushed forward to get the nose down. The fact that it responded showed that there had to be some forward motion. I hardly dared breath as the nose dropped enough to where the airspeed needle began to creep up the dial. I didn’t do a thing more until I could see 200 mph on the dial. Only then did I re-enter the fray.

“The P-39 was very unforgiving of careless handling. Usually, it was a very easy airplane to fly, even the planned stalls were quite normal, but an accelerated stall or unusual attitude could result in some wild unplanned maneuvers. Bell’s test pilots had been asked to try to tumble the aircraft. Not surprisingly, they found it could not be done. However, if an airplane falls like a rock and flops around in all manner of attitudes in the process, then to me that’s tumbling. I’ve tumbled the airplane twice and have watched other tumble at least five times and, as far as I’m concerned, that’s that.”

1st Lt. William O’Brien was one of the original flight leaders in our 363rd Squadron, a position he occupied throughout his combat tour with the Group. He flew 77 missions with 300 combat hours, and is another of those on the ace list. In later years he served as a squadron commander and test pilot. Although “OBee” mastered the P-39 with little trouble, he was never happy with it:

“I was never completely relaxed while flying the airplane, as I considered it aerodynamically unstable, even when you knew where the center of gravity was located, or at least thought you knew. I contended that the C.G. on a P-39 moved around more than a party girl at a company picnic. With a full load of gas, it flew differently than it did an hour later when the fuel burned off. The same was true when flying gunnery, except it got worse as we expended both fuel and ammunition, and the wandering C.G. You could never trim the beast to fly hands off. There are those who say the P-39 won’t tumble, but I’ve seen this “changing ends” occur. The same guys say you can’t drag a tail on landing. It can be done and it cost Tommy Paxton, the Bell representative, a case of beer, because I did it.”

“I remember at Tonopah, I had three ships up doing a little formation work, and looking back over my left shoulder, I saw a single diving P-39 attempting to join, or bounce us, but it did a double snap roll! I thought the pilot must be Colonel Stetson, as no one else could handle a plane like that. When we landed, I was in the Ops room remarking on it, when Ellis Rogers, a new pilot, said, ‘I was flying the P-39 and all I wanted to do was join your formation and when I pulled back on the stick – I don’t know what happened.’ What occurred was a high-speed stall, and a double snap roll.”

On 8 May, 1944, Captain Ellis Rogers was KIA after wing failure on his P-51B.

363rd pilot, Bill Overstreet, who went on to fly an extended combat tour with his squadron, has good reason to remember the 28th of June, 1943. He is the only one to provide us with a first-hand account of an escape from an out of control, spinning Airacobra. On the date, Overstreet had taken off from Santa Rosa Army Airfield, along with three other pilots (he thinks they were Lloyd Hubbard, Hershel Pascoe and Charles Peters) to engage in general rat racing and dogfighting in the vicinity of the airfield.

“At some point in the rat race, I lost control of the airplane, possibly due to an over-control. The P-39 snap rolled to the left, and then tumbled tail over nose, ending up in an inverted spin. At that moment it was obviously time to part company with the airplane. I pulled the release handle for the doors, but they did not separate, possibly due to air pressure on the doors. By getting my shoulder against one door, I was able to push enough to get the door off. I got out immediately and pulled the ripcord. When the chute opened, it slowed my fall at the same instant my feet hit the ground – I landed standing up, didn’t even bend my knees. I landed amidst the wreckage of the P-39, right beside one of the prop blades and among the 37mm ammunition. Since the chute opened below the trees, the rest of the flight went back to base and reported my demise.”

Howard Hinman, who eventually built up a respectable 400 hours in the P-39 and went on to fly a full combat tour, had a frightening, but happier experience. “At Tonopah, I stalled out at the top of an Immelmann and went into a flat inverted spin (there could have been a tumble also). Finally, with full power, I was able to recover from the resulting spin.”

C.E. “Bud” Anderson: “We were briefed that the P-39 had bad stall characteristics and would tumble end over end if you were not careful. I can’t remember much about the stall characteristics, probably I never stalled the P-39 very often. I certainly never tumbled one, but I did watch from the ground while Bill Overstreet went through some pretty wild gyrations during a rat race over the airfield at Santa Rosa. I am sure that after a ride like that, pilots felt they tumbled or did most anything.”

Despite the appalling number of causalities, fatal and non-fatal, the belly landings, bail outs and mechanical failures, in the Summer of 1943, there was a great deal of flying and valuable experience was gained by all. Some 75 enthusiastic, high spirited, very young fighter pilots were having the time of their lives. To show the flavor and spirit of the times, we quote from some of those men who were there and remember.

Leonard “Kit” Carson: “We were assigned to the 4th Air Force and flew some coast patrol and intercept missions. The rest of the time we continued training, shooting aerial gunnery over San Francisco Bay. This was done by the lead ship buzzing low over the water and dropping a bag full of alumina powder, which would split on impact and make a slick on the water and a good target. The bay is 8-10 miles wide at this point, so we had just enough room to maneuver in a gunnery position.”

“We did our best to give the Navy pilots from Alameda a hard time while in their area. We’d do barrel rolls around the whole gathering of blue Grumman TBFs. If there was a gap in the formation, we’d slip into it and fly almost close enough to scrape a little blue paint off onto the Army OD green. The TB pilot would feel something rocking his boat and would look over his shoulder to see a green Army P-39 flailing the ozone with an eleven-foot prop scant inches away from his wing. We’d invariably be wearing our most hospitable cigarette ad smile as he looked us over.”

C.E. “Bud” Anderson, of the 363rd over Oroville: “We flew as much as we could, and every day there were mock dogfights. We flew at night, we flew in formation, and we shot the hell out of ground and aerial targets. We were honed fine and craving excitement. Almost anything went. Oklahoman Joe Pierce, a soon-to-be ace in my flight, buzzed the Oroville runway so low that the prop of his P-39 actually chewed up the concrete. He gathered it together somehow and stayed airborne. The stunt caused some frowns, but Joe was one of the tigers. It took more than a frown to deflate Joe Pierce.” (Joe was killed in action on 21 May 1944.)

2Lt Glenn Hubbard's Yellow tailed P-39 in Marysville, California. Hubbard and Darwin Carroll jumped an eight ship being led by Eddie Simpson. After Hubbard may a pass, he pulled up to close in front of Simpson and Simpson's prop made hash of Hubbard's rudder. Simpson landed normally, Hubbard did not.

2Lt Glenn Hubbard's Yellow tailed P-39 in Marysville, California. Hubbard and Darwin Carroll jumped an eight ship being led by Eddie Simpson. After Hubbard may a pass, he pulled up to close in front of Simpson and Simpson's prop made hash of Hubbard's rudder. Simpson landed normally, Hubbard did not.

“I loved firing the P-39’s 37mm cannon. It was supposed to be fully automatic, but invariable it jammed after two or three rounds. In spite of that, I once destroyed a ground target with just two shells. The cannon was murder on ground targets, a great morale booster! Trying to hit the aerial target was a different matter entirely. To the best of my knowledge, no one was able to hit it with the cannon.”

Marysville to Ainsworth – Via Mexico

With the arrival of Fall, 1943, the California training period came to an end. Orders went out to Group Headquarters and the 363rd Squadron at Oroville that all personnel proceed on or about 4 October to Casper AAF, Wyoming. Eighteen pilots would ferry the unit’s P-39s, everyone else going by rail, except for a few by private auto. Similar orders would have gone to the 362nd at Hayward (to proceed to Pocatello, Idaho) and the 364th at Maryville (to proceed to Ainsworth, Nebraska}.

Because the rail trip took five days, the 364th pilots would fly a long looping course south and then east and north to Ainsworth, in order to arrive about the same time as the rail party. It was during this passage along the southern border that 2nd Lt, Richard A. Peterson, future triple ace and one of the many marvelous characters of the 357th, was to cause a minor diplomatic incident. The 364th contingent had RONed (Remain Over Night) at Los Angeles and the next day pressed on to Phoenix without incident. With the P-39s secured for the night, it was party time for the pilots, as it had been the night before at Los Angeles. Peterson remembers, “We headed for the Westward Ho Hotel. As usual, we attempted to relieve the bar of all its assorted bottled goods and also attempted to provide the local females a thrilling evening by rubbing elbows with the Army Air Corps’ most genteel and anointed group of fighter pilots. The hours began to take their toll. We were up again – not so bright, but terribly early – pre-flighted the P-39s and were on our way.”

The route on this third day was via Tucson, destination Riggs Field, El Paso. The P-39s were in no particular formation, just loose gaggle and using the airways radio for navigation. Peterson takes up the story: “The all-night carousing, the warm sun in the cockpit and the steady drone of the engine began to have an effect. I got a little drowsy, loosened my parachute leg straps and put my feet up on the cowl gun butts and laid my head back – flying on the belly tank. It must have been about five minutes or so when I finally came back from the catnap and discovered that all those other planes were lost. I could not see them anywhere.”

Unable to bring in any radio beam signals, Peterson dug out his maps, but soon discovered that they were useless, since there was nothing in sight but desert in all directions. Low on fuel and ideas, he decided to fly east and land at the first sign of civilization.

“About this time, in the distance, I saw a cluster of about 6 or 8 shacks with a road leading up to them. The road had just been graded and was about 3,000 feet long – perfect! I decided to land going into town, that way I would not have to walk. When I dragged the road to check out its condition, I was so intent on the road, nothing else mattered and, since we had practiced enough short field landings, this would be a piece of cake. I peeled up, dropped my wheels and full flaps, chopped the mixture and cut the engine for an easy dead stick landing I dropped onto the road and came over a slight rise in the ground. Gawdamighty! There, about 500 feet dead ahead, was a siding of freight cars that seemed to appear out of nowhere, I was doing about 80 mph and slammed into the rail cars with the left wing just outside the left landing gear, shearing the wing off at the gun mounts. The shock spun me around and tore off the right gear. I sat in a cloud of dust in the middle of El Chapo, Chihuahua, Mexico.”

Besides a string of boxcars blocking Peterson’s chosen runway, El Chapo had a rail and telegraph station, which he used to contact Operations at Biggs Army Air Field. In due course an Air Corps lieutenant arrived from Marfa, Texas, and the Mexican police also showed up to confiscate the machine gun ammunition and the 37mm cannon shells.

After the lieutenant bought beer all around and smoothed over the fact that Peterson had used illegal U.S. currency to send his telegram, a local photographer showed up to record the wreck. The two lieutenants then returned to Marfa. (Peterson never saw any of the photos.) What was probably the most exciting day in a long time for El Chapo was over, and Peterson continued his trip to Ainsworth by rail.

The other two squadrons followed similar routes, but no one else ended up in Mexico, except Bud Anderson, who walked across the border in El Paso to obtain a bottle of tequila for his crew chief.

Upon arrival at 2nd Air Force bases, it became obvious to even the enlisted types who, despite rampant rumors, never knew what was going to happen until someone said, “get on the truck,” that training time was running out.

Most of the work that month of October was on the ground, where the squadrons were preparing for final inspection and overseas deployment. While this was going on, the pilots continued to build up hours, but now most of it was in mock combat with the B-24s. The skimpy records of the period mention only three incidents.

On the 16th of October, Flight Officer Chuck Yeager found the landing gear would not extend on Bud Anderson’s Old Crow, and he set it down on its belly at Casper Arm Air Field. So ended the service life of the first Old Crow; Anderson’s 2nd and 3rd Old Crows would be more famous.

The next day, the Group Commander, Colonel Edwin Chickering collided with Lt. Don Currie during a gunnery pass at a B-24. Currie managed to land and the colonel bailed out successfully.

The last recorded incident in the records again involved the soon-to-be-famous Chuck Yeager, when he bailed out of a burning P-39.

The Final Tactical Inspection in late October said: “Combat fitness of training, personnel, and equipment is considered very satisfactory and the unit is recommended for O/S (overseas) movement on readiness date.”

Training was over, The year just ahead – 1944 – in the deadly skies of Europe, would provide little of the fun that the summer of 1943 had been in the peaceful skies of California, and there would be a lot more casualties.

To War – In A P-39

During the eight months the 357th Fighter Group trained with the Bell Airacobra, its 75 or so pilots had a wide variety of experiences in the little beast. However, only the three squadron commanders, Captain Hubert Egnes, Varian White and Thomas L. Hayes, Jr., had combat experience, and only Hayes in the P-39. Hayes took command of the 364th Squadron in May 1943, after his return from the Pacific.

On 7 December, 1941, Lt. Hayes had been with the 70th Pursuit Squadron at Hamilton Field, Calif. long enough to accumulate a respectable 300 hours in the Curtiss P-40. Ten days after Pearl Harbor, Tommy Hayes and 54 other “combat teams” (one P-40, one pilot, one crew chief and one armorer) were on their way to Brisbane, Australia. Here, the P-40s were assembled and their teams moved on to Java in a futile attempt to stop the Japanese tide. Shot down during this period, and after a hospital stay to recover, Hayes joined the 35th Fighter Group, then working in Australia, in the early spring of 1942. The group was equipped with P-39s and P-400s (the export version of the P-39, roughly equivalent to the P-39D-1) and it was here that Hayes had his first encounter with the Airacobra:

“First impression – what great visibility! In the P-40E, with its long nose obstruction vision, the pilot had to “S” along the taxiway. In the P-39 you drove it straight, like a car. My first flight was an orientation, I was not out to prove or disprove the horror stories of flat spins, inverted spins and tumbling. That would come later. I enjoyed the flight. With the P-39 you learned to walk before you ran. With each flight it became more fun.”

“By mid-1942 the 35th was in New Guinea operating from strips outside Port Moresby on the west coast, separated from the Japanese by Owen Stanley mountain range, which rose to 11,000 feet and ran down the spine of the big island. The Japanese were operating from the east side with bases at Lae and Selamua. Since radar is line-of-sight, we received little warning when they attacked the Port Moresby complex. Because of the P-39s slow rate of climb, engagement before bomb release was almost impossible. Usually, while we were still climbing, their bombs were dropped and the bombers and escort fighters were nose down on the way home. “

“When we did engage the Japanese, the P-39 usually came out the loser. With its high-wing loading, the P-39 could not turn with the Zero. Like the P-40, we had to make hit-and-run passes. You did not dogfight a Zero in the classic manner with a P-39. If you let the engagement evolve into a dogfight the P-39 was going to be shot down, if its pilot had not already overcontrolled and augered in.”

“Without warning, the P-39 could be downright vicious if a pilot made any mistake, no matter how small. On the other hand, if a pilot made a similar mistake, or even a bigger one in a P-40 or P-51, the aircraft would make its own correction or alert the pilot to the problem. To put it another way, if the aircraft could talk, the P-40 and P-51 would say, ‘Whoa! Back off.’ The P-39 would say, ‘I’ll kill you for that.’ And she did! Limericks and ditties were coined and sung such as, ‘It’ll tumble and spin and soon auger in.’”

“Despite its weaknesses, I feel the P-39 was an excellent training aircraft. I strongly believe that pilots who trained in the P-39 were better for it.”

Lt. Colonel Darrell Cosart, USAF (Ret.), was not a member of the 357th Fighter Group, but is a local friend of this writer, and a fellow member of the late, great Colonel Hub Zemke’s “lunch staff.” Cosart’s extensive combat career is well worth including here to provide a bit more depth to the story of the P-39 in combat:

“Having recently graduated from the flight school when the war began, I was assigned to the 70th Pursuit Squadron of the 35th Pursuit Group at Hamilton Field. On 12 January, 1942, my squadron set sail for the Fiji Islands with 24 crated P-39s in the hold. None of us had ever flown one before.”

The 70th Squadron flew air defense and trained itself for some ten months on Fiji, where Cosart built up some 300 hours in the P-39, including one encounter with its vicious nature (snap rolls and several spin reversals, before a normal recovery).

“In December of 1942, part of my flight moved to Guadalcanal, where the real thing was going on. I think most of us were quite comfortable with the P-39, and knew what we could and could not get away with. I felt the P-39 was quite easy to fly and responded to the controls nicely. The negative part of the flying the P-39 was our inability to turn with Japanese aircraft and the plane’s altitude limitation, which was a real drawback. Strafing and bombing of enemy troops and shipping was our mission, but we also flew escort for B-26s bombing Munda, on New Georgia, and for B-17s bombing Japanese destroyers coming and going in “the Slot.”

“My first B-17 escort mission was the second of the day for the 70th, the first having lost two P-39s in a scrap with escorting Zeros. It took us about an hour to reach the target destroyers and it seemed like four hours of wondering where the opposition would be when we arrived.”

“As we approached at 10,000 feet, we could see dark specks over the destroyers, which turned out to be Nakajima E8N Type 95 ‘Dave’ biplanes with a rear gunner. I was a wing man, and as my leader headed for one, another came in from my right side, so I turned into him. I started firing and his top wing started to come apart as he passed below me. The rear gunner seemed very close! I saw another, but he dove away before I could fire, and when I rolled to follow, my turn was so uncoordinated, that dust swirled up from the floor, blinding me momentarily. I swung around and there were planes everywhere, all ours, with pieces of enemy planes and parachutes going down. In that minute and a half encounter, we had shot down all of them, and I got credit for one.”

“We didn’t get many chances for air-to-air with Japanese planes, but my most exciting day was 7 April, 1943. It was my day off, but there were reports of enemy aircraft coming down the Slot, so I took off as wing man to Captain Waldo Williams. Lt. Bill Daggett made it a flight of three. We were at 10,000 feet and we got into a turning circle. I was pulling it in so tight I was getting vapor trails from my wing tips. We made five or six turns and I fired a burst whenever I had a chance, my tracers seemingly going right into the Val, but without results. In the meantime, we were getting lower and lower and the two remaining U.S. Destroyers were firing at both of us. Finally, recalling the high-speed snap I had experienced a year earlier, I rolled out of the circle and turned to locate the Val. No aircraft were in sight, only a churned-up area of water where something, probably my Val, had gone in. I waggled my wings at the destroyers and left the area. Since there were no available witnesses, I never got credit for the victory.”

“I flew the P-39 for almost 500 hours, about 180 of them in combat. Compared to the P-51, P-47 and P-38, the P-39 was quite a dog, but I found it a nice flying airplane and it did get me through two combat tours! After returning to the states in May of 1943, I flew all the major fighters, including the Bell’s improved P-63 Kingcobra, and could not help but wish we had had them during my two tours on Guadalcanal.”

There is a remarkable agreement among surviving pilots of the 357th Fighter Group who trained in the P-39. All say they loved flying the aircraft, and several suggested this might be because it was the first fighter they had flown. It was a fun airplane, once mastered, for a group of very young men who were thrilled by its power, noise and speed. All commented on how the superb visibility from the cockpit and the tricycle landing gear made taxiing, takeoff and landings very easy. Even “OBee” O’Brien, who is most adamant in his condemnation of the P-39 as a fighter and an airplane in general, admits that, like everyone else, he loved flying it. All agree that it made an excellent fighter trainer, due to the fact it was so difficult to master. All of them were, and are, well aware of the Airacobra’s shortcomings, and none expressed a desire to fly it in combat. Some were downright ecstatic they did not have to.

Undoubtedly, the aircraft’s major shortcoming was its lack of high-altitude capability. Most postwar writers attribute this to Army stupidity in removing the originally planned turbosupercharger, leaving only the Allison’s dismally inefficient internal blower. The reasons behind the turbo removal were not that simple and much more complex. These same postwar writers also blame the airplane’s performance shortcomings on the Army, which they say took Bell’s marvelous XP-39 and ruined it by adding on so much extra equipment. They never tell us what this unneeded equipment was. The XP-39 certainly did have remarkable performance for the late 1930s, reaching almost 400 mph, 20,000 feet. However, it was in no way a military aircraft, as it had no guns, armor, self-sealing fuel tanks, or other operational equipment. These are the “extras” the Army is accused of adding.

By the time the 357th crossed paths with Bell’s little rasper, it was already well established as a low-altitude fighter. However, this handicap had no real impact on the 357th training, which did not stress the high-altitude aspect. At Tonopah, in fact, almost all flying was done on the deck. The major impact on the 357th seems to have been the sometimes-vicious nature of the beast. Many pilots had a delicate touch on controls and had no trouble with the P-39. Others were forcibly reminded that the P-39 was a touchy little bird. Leonard “Kit” Carson, destined to be the highest scoring ace of the 357th, had this to say in his book, Pursue and Destroy.

“I had my head rattled against the sides of the canopy twice by violent motion of the airplane in high-speed snap rolls, before I got wise. This happened on gunnery passes at an aerial tow target while closing from too large an angle and trying to pull the ‘39 in tighter so as to hold the proper lead on the target. The ship would go into a high-speed, buffeting stall for a split second and then, because of back pressure on the stick, go into a violent snap roll for as many turns as it took for you to release the pressure on the stick. Aside from that characteristic, it was a fun airplane to fly and quite unique in design, but useless as a weapon above 16,000 feet.”

Despite the fact that most pilots tamed the P-39, the casualty list and the near catastrophes seem to confirm that many horror stories that circulated during the war years and to this day, “It’ll tumble and roll and dig a big hole” was not just an officer’s club barroom song.

Perhaps the 357th experiences with the P-39 Airacobra is best summed by the always expressive Bill “OBee” Obrien:

“As a trainer for fighter pilots, I would rate the P-39 as excellent. The reason being that the plane was so unforgiving. If you could handle this plane properly, it then became obvious that the pilot possessed a satisfactory degree of competency. There was nothing to compare with the precision of a four-plane flight’s tactical approach: coming in a 50 feet elevation, 250 mph indicated airspeed, in echelon to the leader’s right, and when he crossed the end of the runway, seeing the P-39s racked into a climbing chandelle with out power, pulling streamers from the wing tips, each plane following and spaced so all four were rolling on the runway at the same time. That was fun and flying!”

“I believe that most of our P-39 crashes were due to the pressure created by the fact the U.S. entered the war totally unprepared. We had to train extremely hard, in a minimum of time, using complex equipment. The result of those conditions was that our training losses were in actuality – combat losses. Just think of what we accomplished. We didn’t have anything to start with, and yet, in three short years, we were successfully destroying not one, but two exceedingly and highly respected air forces.”

Tonopah, NV today!

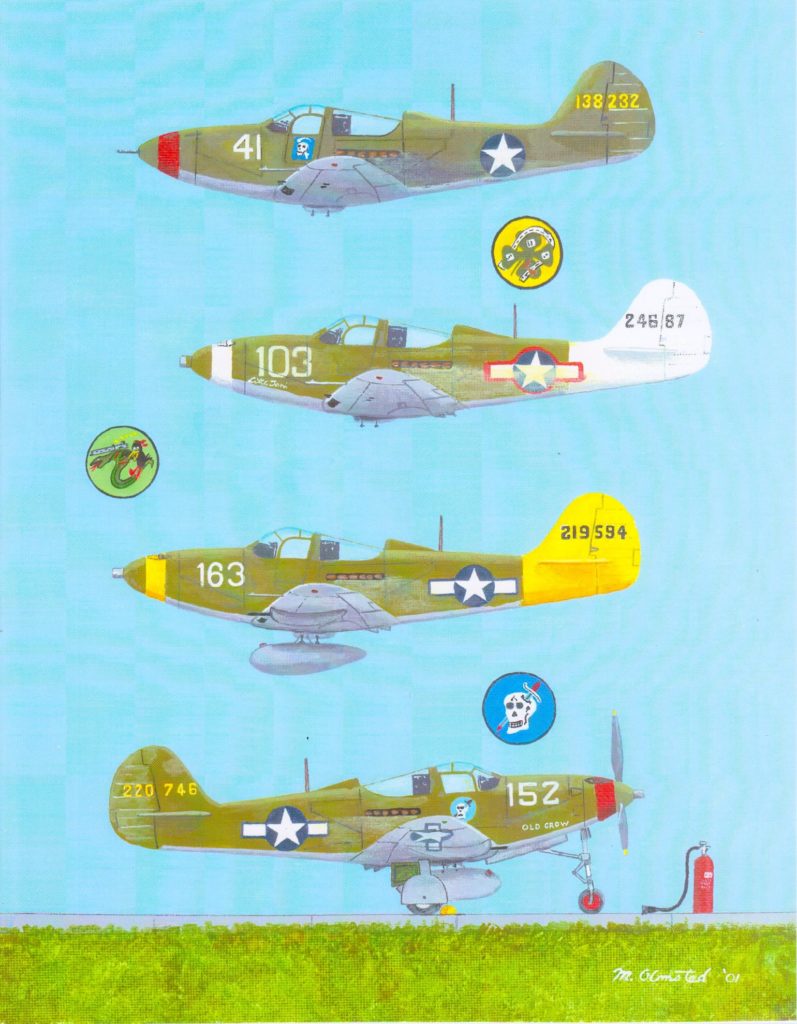

357th FG P-39 Art by Merle Olmsted