WWII Aerial Gunnery by Triple Ace CE ‘Bud’ Anderson

Captain CE ‘Bud’ Anderson gun film, 27 May 1944, victory against an ME-109.

“The best shooting method for us seems to be to get in as close as you can and still avoid hitting his plane or any pieces that by chance may fall off it and let’er rip. Anyone will do his best shooting when he is so close that he cannot miss.” 364th FS Commander, 357th FG Ace, Major John Storch

There is no such a thing as an average dog fight. They are all different! It’s like a card game; you are dealt a hand and have to play with the cards you received. You had to learn in training how to deal with many different situations, so you could react instinctively. Ace OBee Obrien, likened an aerial dogfight to a knife fight in a dirt floor bar. During combat in WWII, we did not have radar or guided missiles. All engagements were close in with guns only. Good eyesight was an important factor for success. I was blessed with exceptional vision, 20/10 in one eye and 20/15 in the other, which helped me be successful in combat.

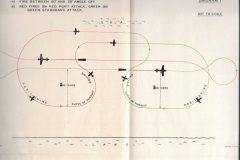

While in Advanced Flying School, as part of our training we flew to Ajo, AZ, where there was a bombing range. We were flying the North American AT6 Advanced Trainer. We mounted one or two 30 caliber machine guns, one in the right wing and another on top of the fuselage in front of the wind screen. We fired at ground targets and also at targets being pulled through the air behind a tow plane. The tow targets were either a rectangle screen or a 360 degree sleeve with a ring at the front to keep the target inflated. (Much like a wind sock) Our ammunition had the tips painted in different colors to identify the shooter. While shooting at the tow target, we flew left and right hand pursuit curves.

After considerable time flying the P-39 in the 357th FG, I was sent to Texas, where there was a special aerial gunnery school. This was an attempt by the Army Air Corps to duplicate the aerial gunnery school of the Royal Air Force. This was well organized and featured the use of gun cameras to analyze range and angle off to target.

When I went to England and started to fly the P-51B, I was sent to the RAF Gunnery Instructor School at RAF Wood Bridge. I was allowed to fly my P-51B to the school, instead of flying the Spitfire. This allowed me to gain more experience in the Mustang before combat. This course emphasized analysis of the gun camera film. One thing I learned at the school was that we were all firing out of range. Once you got a target in the reticle, it was very hard not to pull the trigger. This was a good lesson to learn before combat, to wait until you were in range.

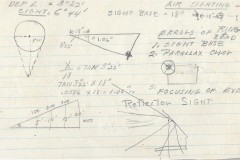

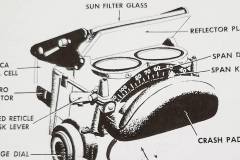

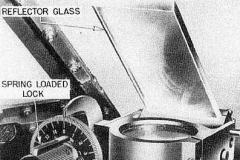

The P-51B had four 50 caliber guns, two in each wing. We used a fixed sight N-3 or N-9, so we had to calculate our own firing solution. Later we got the K-14 lead computing gun sight, which solved some of that problem for us. I shot down more enemy aircraft with the fixed sight, however the use of the lead computing sight was probably a benefit for our new pilots. I was the first one in our group to receive the K-14 Gun Sight mounted in my P-51B. I underwent training on the employment of the sight and then returned to Leiston to train our group pilots on the new system. I published a small manual on the K-14 and briefed all the squadrons on its use. Basically on the way it worked! The sight had a pipper with 8 diamonds around it, which were controlled by a rotating motorcycle type handle on the throttle. The idea was to track the target with the pipper and match the diamonds with the wing span of the target. Then the pipper would move forward to the proper firing solution. You would then continue to track the target and fire.

My P-51 with the fixed sight was harmonized at a point at 300 yards. With the K-14, my guns were harmonized in a box pattern at 300 yards. The box pattern was to help the average pilot be more effective. I preferred the single point harmonization, but the 8th Air Force regulations required the use of the box pattern for the K-14 sight.

When the P-51Ds became available, they had six guns, three per wing, which improved our fire power. But in general, we had about 30 seconds of firing time, so you had to be cautious and use short bursts to preserve ammunition.

Initially our P-51Bs had problems with gun jams. We learned that the guns had to be absolutely clean and not oiled, as the oil could freeze at altitude. Another problem with the B model guns was that they were mounted on a slant in the wing, which could cause a gun to jam. The P-51D fixed that problem by having the guns mounted vertically. Our P-51B’s normal load was 350 rounds for inboard guns and 280 rounds for outboard guns. The P-51D held 400 rounds for each of the two outboard guns and 270 rounds for the center and inboard guns.

There was an armorer assigned to each P-51 to take care of the ordinance. He loaded and maintained each of the 50 caliber guns. My armorer was Leon Zimmerman, who performed in an outstanding manner. I did experience gun jams in the B model, but never in the D.

CE ‘Bud’ Anderson

After arriving in the United Kingdom, Captain Bud Anderson was selected to attend the RAF Gunnery School at Sutton Wood. This was very fortuitous, in that he got additional hours in the P-51B and was able to hone is aerial gunnery skills before flying his first combat mission.

Some of Bud’s gun camera film from RAF Gunnery School