WILLIAM R. O’BRIEN “Obee”

Born Tulsa, 14 Nov 21.

Military service: Oklahoma National Guard 1938; Aviation Cadet Jan-Sep ’42. Active duty 1942-46 and 1947-48. Discharged from USAF Reserve 1957. Combat: 300 hours in 77 missions with 363rd FS, 357th FG 1943-44. 5.5 e/a confirmed destroyed, 2 probably destroyed. Awards & Decorations: 4 DFCs, 8 Air Medals, French Croix de Guerre. Obee was an original member and flight lead with the 363rd FS, 357th FG “Yoxford Boys.”

WHAT WAS PILOT TRAINING LIKE?

I entered flight training with Class 42-I consisting of Primary, Basic, and Advanced phases over a nine-month period. Primary and Basic were taught in Ontario, California at Cal-Aero Academy by very competent civilian instructors. They were contracted to the Air Corps (Army Air Forces) to train pilots. Advanced phase was taught by Air Corps officers at Luke Field, Arizona. The primary training plane was the Stearman PT-17 with a 225-hp engine. Basic used the Vultee “Vibrator” BT-13 and the North American “Texan” AT-6 was the choice for Advanced. Pilot training was rigorous both in mental and physical aspects. About two-thirds of all preflight personnel were eliminated from pilot training. Physical requirements were set quite high utilizing the Air Corps (64) physical tests. Acceptance as an Aviation Cadet was restricted to those with a minimum two years of college. These were the prewar standards when I enlisted. After passing the stringent physical requirements, I was sent home to have dental work. This work was done at my expense in December 1941 ($50). The dental work had to be completed prior to being appointed a Cadet in January 1942. We may have been losing the war, but the Air Corps at Ft. Reiley, Kansas, was still manned by peacetime people. They operated with holdover attitudes, hence no changes were permitted in the appointment process.

HOW MUCH ACADEMIC WORK WAS INVOLVED?

We spent about half our time in class work. We learned aerodynamics, gunnery, map reading, etc. The other half of our day was spent flying, doing physical training, guard duty, etc. The program did not provide free time for cadets; it was work, work, and run, run.

HOW WERE PILOTS SELECTED TO FLY FIGHTERS OR BOMBERS?

Apparently our civilian instructors made recommendations to the ever-present Air Corps check pilots as to whether we should be sent to single- or multi-engine advanced flight school. As cadets we were never consulted as to our future. I was delighted to get to single engine school because I had always wanted to be a pursuit pilot.

WHAT WAS FIGHTER TRAINING LIKE?

Simple: read the airplane manual, start the engine, and fly the airplane.

HOW WAS FLYING THE P-39?

I could write a book about this, but thank God someone else did. The book is “Nanette” by a man named Park. He, like me, thinks the damn thing had a soul. The P-39 was undoubtedly the worst airplane the Air Corps had in its inventory. But if a pilot could accumulate about 150 hours, he should be awarded a medal, as he is well on his way to being a fighter pilot. That particular airplane was absolutely unforgiving and aerodynamically unstable. It was so bad that many service pilots did not, or more likely, would not fly it. Tactical units had members sent to the manufacturers to fly P-39s to their units. I know this because I was one of the lucky ones who got to do this type of work.

WHAT TYPE OF TRAINING SORTIES WERE FLOWN?

Formation, ground gunnery, and night.

HOW WELL WERE YOU PREPARED FOR COMBAT?

Very poorly, but for the good reason that none of our superior personnel had combat experience.

HOW WERE ORIGINAL FLIGHT LEADERS SELECTED?

I believe that the cadre of flying personnel were selected on the extent of their experience in the P-39. Those pilots in the 328th FG of the 4th Air Force with the most P-39 flying time were candidates to join the 357th FG. The group commander could pick from a personnel list meeting those requirements. Remember this: personnel had no combat experience at group level. You were fortunate to get combat experienced squadron commanders at a later date.

WHAT TYPE OF TRAINING DID FLIGHT LEADS RECEIVE?

None. I repeat–none. As in most wars in which America participates, the old crutch of on the job training gets the job done. We took casualties because we had neither the trained people nor first class equipment. With time we trained ourselves, but the price was high. We lost good men because of training deficiencies in instrument flying, aerial gunnery, and organizational errors. There was no reason to have a “Clobber College” at the 357th Group or at Goxhill in England. We, like most of the armed forces, had to make do with what was available. Much of the success of the 357th can be attributed to the initial cadre, as they had to train themselves and the rest of the group. A large amount of diversified flying time is significant in selecting personnel for leadership roles in any air force. Those in command who don’t or won’t train their men properly should be assigned to burial details.

WHAT WAS YOUR TRIP TO ENGLAND LIKE?

The trip from New York Harbor to the River Clyde in Scotland took four days. The Queen Elizabeth sailed at 30 knots with 14,000 men aboard, in the foulest of weather straight to Britain. The trick was, holding the 30 knots and in knowing that all bad weather eventually gets to England. The British did a fine job to feed us all twice a day and getting us there.

WHAT WAS YOUR IMPRESSION OF ENGLAND UPON YOUR ARRIVAL?

It was dark and wet when we arrived. It stayed that way for most of the year I spent in England. When I went to a large city like London, the destruction was evident. The debris created in 1940 had all been removed but the “Little Blitz” and the “buzz bombs” occurred while we were at Leiston. The unsettling effect on the local people was observed after a raid. Night fighting involving the RAF was visible from our base and being in London during the buzz bombing got your attention. I admire the English population. They were not meek, just relatively quiet and determined. They were underfed and had suffered much. They are a good people but at times poorly led.

WHAT WAS DAY TO DAY LIFE AT LEISTON?

A typical mission day consisted of being awakened before dawn by the orderly saying, “Briefing at 9:00.” So we’d crawl out of our warm cots, brush our teeth and put on some kind of uniform and head for the mess hall. If you were lucky you carried the combat (government-issued) egg in its shell. At the mess hall you got your egg cooked for your breakfast of bacon, toast and coffee. Then, to the rest room of the adjacent officers’ club where hot water was available so you could shave. We would check with “Smitty,” our operations clerk, who knew everything about who was flying and in what. Flight leaders usually flew with their flights every mission. All flight members had been alerted the night before. Those who were flying that mission had their names and plane assignments listed on the “ops” blackboard. Then it was off to group headquarters. There we were told by the mission leader where we were going, courses to be flown, start engine, takeoff and rendezvous times for bomber intercept, anticipated weather, and expected opposition. Next we went back to the squadron ops area, got our flight gear on, visited “that little room” and met Smitty for a ride to our planes. I knew where my flight was to form up in squadron formation. We positioned ourselves, taxied into takeoff position, and began the mission. Usually we got back home in about four hours. If no further missions were scheduled, after squadron debriefing it was off to the O-club to discuss with everyone how things had gone. Whatever uniform you wore was OK for evening mess, which was usually C Ration stew. After dinner we’d have a few drinks and then to the Nissen hut that was home. Hollywood’s ideas to the contrary, I didn’t see combat people drinking excessively. The work was hard enough with a clear head, and no one will work in combat with a drunk. If there were air raids or buzz bombs in the area, we would watch the action possibly from a slit trench. Usually our lights were out about 9:30 and so were we.

HOW OFTEN DID YOU FLY?

In the seven months from February through August of 1944 I flew 77 missions involving 300 hours of combat time. This works out to about 11 missions a month. That number sounds like a fair guess. Our work was dependent on weather and equipment availability. Our local weather conditions for takeoff did not greatly influence Fighter Command’s decisions. If 8th Air Force and Bomber Command had available aircraft an a target, we supported the operation. If not an escort mission, then a fighter sweep may be ordered by fighter wing command. I have seen overloaded P-51s taking off on a combat mission, during a snowstorm, with the end of the runway invisible from the cockpit. As flight leader you started on instruments. With luck you would break out on top of the cloud deck at 2,000 or 3,000 feet. I have also climbed to 20,000 feet still in clouds. So you could never depend on the weather forecast. Best assume that the weather would be bad and prepare accordingly. Equipment problems consisted of replacing losses and repairing battle damage.

WHAT OTHER DUTIES DID YOU HAVE OTHER THAN FLYING?

I had no other assigned duties at Leiston.

DID THE SQUADRONS FLY TRAINING MISSIONS FROM LEISTON?

We did not fly squadron training missions in England.

HOW GOOD WAS INTELLIGENCE ON ENEMY TACTICS AND CAPABILITIES?

Intelligence reports of US origin were nonexistent. I believe that the British had extensive information, some of which they published in a “red” pamphlet. It was interesting, as it discussed personnel, equipment, unit transfers, etc.

DESCRIBE A TYPICAL MISSION

All missions were prepared for based upon the experience and normal duties of the pilots involved. In my case they were all handled about the same. I required pilots in my flight to fly their aircraft in a competent manner. They were disciplined to maintain formation. they were always vigilant in their sky search for enemy aircraft and to protect their element and flight leaders. When possible, attract the enemy. These actions were visible evidence of good airmanship resulting from adequate training. The lead squadron departed in pairs. They flew a large circle allowing subsequent squadrons to form on them. The low squadron formed up on the lead squadron’s left or up sun side. The high squadron occupied the down sun side or remaining position. Our tactical formations had separation of about 200 feet between planes and elements. We climbed on a given heading with airspeed of 165 mph. If reduced visibility required the flight leader to go on instruments, the separation between planes was tightened up so a minimum distance existed. Flight leaders flew on instruments with flight members flying formation on the leader. Not a good way to climb out with about 50 airplanes, but that was how it was done. Initially, fighters were charged with protecting the bombers. That meant you flew fairly close to them, certainly where you were easily visible to them. Tactically this changed when General Doolittle took command of the 8th Air Force. When he assumed command we were ordered to destroy the German Air Force. German tactics had changed basically to “company front” head-on attacks against the bomber stream. This required that we support the bombers by positioning well above and far in front. By doing this we could engage German fighters before they could get close to the bombers. Great Britain, being about 800 miles long and 150 miles wide, made it easy to find in good weather. In bad weather it was an entirely different story. The 357th FG had its home in East Anglia, a flat country from a topographic viewpoint. I don’t think there is 100 feet of relief from London in the south to the Wash in the north. It would compare to the Gulf Coast topography of Texas and Louisiana. This suggested that an instrument letdown could be made fairly safely down to 1,000 feet over the sea or land. On 20 February 1944 Lt. Donald Ross, on loan to us from the 4th FG, led my flight (because he had combat experience and I did not). I led his second element. Then my wingman had to abort. We now had a 3-ship formation. Lt. Ross leading, Lt. Albert Boyle on his wing and Capt. William O’Brien (me) as second element. Lt. Ross was lost in combat that day. He had to bail out after hitting debris from an Me-109 that he had destroyed. The fighting was over and I had Boyle on my wing as we headed for England. The closer we got to the North Sea the worse the weather became. We were flying above dense clouds. Within 75 miles of base, radar could give us a heading to Leiston. After contacting the base they reported the weather, “Oranges are sour.” They gave me a heading to base. I asked, “How are the oranges?” They replied “Six.” This meant the cloud base at Leiston was 600 feet and required instrument letdown. No beam or additional guidance was available. Dropping 20 degrees flaps and throttling back to hold 220 mph airspeed, I let down till the altimeter read 500 feet. At last, I could see the ground and we were about five miles southeast of Leiston Field. After landing and parking on my hardstand, Jim Loter, my crew chief, started to climb on the wing to assist me out of the cockpit. I asked him to wait. I was physically shaking like a person with a chill. In a minute or two I had control of myself and exited the plane to join Smitty who was collecting the returning pilots. Al Boyle, who was on my wing said “That was swell, “OBee. How did you do it?” My answer was “Nothing to it, Al.” This of course was a tremendous lie, as the hand of God was clearly evident. We could have been anyplace, but such are the fortunes of war.

WHAT WERE THE DIFFICULTIES IN JOINING UP LARGE NUMBER OF PLANES?

The main problem was weather. If the cloud base was 1,000 feet or higher, the group could form up below the clouds. A lower base required flights to penetrate the clouds on instruments and forum up above the clouds. Flights could form up on their leader during a half circle of turn. Formed squadrons could assume their positions with respect to the group commander within a larger circle flown by group lead. Early aborting aircraft could cause a problem unless the stricken pilot used his head and landed without disrupting aircraft taking off.

HOW DID YOU AVOID MIDAIR COLLISIONS?

Unfortunately, we did not always avoid collisions. My flight and that of Capt. C.E. Anderson collided once. We both lost fine men that day. From Anderson’s flight the casualty was Lt. S.R. Guitierez, and from my flight Lt. W.R. McGinley. This points out a problem that existed with the climb out procedure. The problem required an immediate solution. Following this unfortunate experience, I personally flew to the west of base after takeoff with my flight for about three miles, then I turned east and climbed to join the group prior to European landfall.

WHAT WERE YOUR TACTICS FOR BOMBER ESCORT?

Initially we flew about 1,500 feet higher than the bombers at a location from their 3 o’clock to their 9 o’clock positions. As our cruising speed was much greater than theirs, we usually made large S turns over them. However, you needed to be careful, as bomber crews are like the navy–they will shoot at anything. German tacticians desired to destroy the bomber formation integrity. They wanted to concentrate their work on stragglers or damaged bombers that did not have much mutual firepower support. This desire led to the head-on or company front attack by single-engine fighters. German aircraft sometimes operated in gaggles of up to 100 aircraft and were vectored to intercept by ground radar. This resulted in our tactical decision to operate higher and well in front of the bomber stream. It allowed us to intercept the Germans before they could attack our bombers.

WHAT WAS IT LIKE IN AN AIR TO AIR ENGAGEMENT WITH LARGE NUMBERS OF AIRCRAFT?

Large numbers of aircraft in and of themselves did not cause a problem. The 8th, 9th, 12th and 15th Air Forces (the latter based in Italy) were all operating over Europe at the same time. These large operations were conducted with few problems. I remember flying six missions to Munich in a seven-day period. These missions were timed to run 800 to 1,000 8th AF bombers over the target before the 15th AF bombers arrived on target. I remember seeing the incoming 15th bombers getting to the target area as the 8th bombers were withdrawing. The timing and co- ordination usually went well. There were thousands of planes airborne over Normandy during the invasion and the breakout period. Due to good operational planning and timing, these missions were conducted without interference or incidents between groups. However, occasionally the sky became a little crowded. Once during an instrument letdown over France my flight encountered local turbulence. I attribute the turbulence to prop wash from a bomber formation. Obviously, I didn’t know we were operating near any bombers. This particular bombing mission had been ordered to abort and was recalled. We arrived in the same place about the same time, but luckily nobody was hurt.

OF THE AIRCRAFT YOU SHOT DOWN, WHAT TYPES WERE THEY?

Five Me-109s, one Me-110, and one FW-190.

HOW SOON AFTER A MISSION DID YOU REVIEW YOUR GUN CAMERA FILM?

Initially our gun camera films were scarce. Moisture on the camera lens usually became ice at altitude and this severely effected the film resolution. Time was not a problem in reviewing the film.

HOW WAS A KILL VALIDATED?

Supporting statements of wingmen and the pilot’s report were sufficient.

DID YOU EVER HAVE ANY CLOSE CALLS?

Like all who have been in combat, sometimes you are the attacked and not the attacker. Four times my flight or I have been the object of German attacks. Each instance resulted in casualties to both the American and German forces involved. I believe that bad weather and light flak were the greatest causes of death to single-engine fighter pilots of all nations who fought in Europe.

WAS YOUR AIRCRAFT EVER HIT BY GERMAN FLAK?

Yes. My plane suffered a small shrapnel hole in the fuselage, caused by a flak hit during a mission to Berlin.

HOW RELIABLE WAS THE P-51?

I never had serious trouble with the reliability of the P- 51. That Merlin engine was just wonderful. Initially, the P-51B did not have enough oxygen for the long missions required in bomber escort. We would run penetration missions at a lower altitude, making less demand on the limited oxygen. We would then have to climb above the bomber altitudes as we neared bomber intercept. The P-51D had ample supply of oxygen.

DID YOUR GUNS EVER MALFUNCTION?

I’ve had all my guns jam in an air fight when flying the P- 51B. Due to a small wing chord (profile?) the .50 caliber machine guns were canted from vertical to fit in the limited space. With a combination of high speed and G forces, ammunition could not overcome the local elevation rise along the feed path necessary to feed the cartridges into the receivers. This problem did not exist in the P-51D where the guns were mounted upright without being canted.

WHAT MODEL P-51 DID YOU PREFER?

I preferred the P-51D which corrected all the errors of the B model. I shot down seven German fighters using the P-51B. I didn’t shoot down any aircraft from mid May to August 1944 when flying the P-51D. I don’t know if this was caused by bad luck or a German policy of engaging only with an advantage existing for their benefit. The bubble canopy on the D improved vision to the rear. However, the old B with a Malcolm canopy wasn’t too bad. You could read your plane’s serial number painted on the rudder. The guns on the D did not “drop out” and there were six .50 calibers instead of four in the B.

WHAT TYPE OF TRAINING DID YOU GET ON THE K-14 GUNSIGHT?

We started with the optical 78-mil sight backed up with a mechanical post and ring. the 78 mil sight was replaced with an optical ring with radii calibrated to represent a distance equivalent to X mph at a boresight distance of 300 yards. I believe this sight was of naval origin. (Ed. note: similar to the USN Mk VIII sight with 50 and 100-mil rings.) To use the K-14 sight you had to adjust the pipper by calibrating in the wingspan of the enemy aircraft. It was done by rotating a sleeve grip which surrounded the throttle with your left hand. It took time and practice to learn the proper co-ordination to be effective with this sight. I didn’t think all this was necessary to accomplish destruction of an enemy aircraft. Extensive training time was not available. I didn’t use the K-14. Shooting someone in the back with a bunch of .50 caliber bullets will destroy them.

DID YOU FLY ANY AIR TO GROUND MISSIONS?

Yes. Skip and dive bombing missions were flown, primarily after the Normandy invasion. Strafing ground targets was a common mission after June 6, 1944. After Gen. Doolittle assumed command of the 8th AF, a grid system was imposed over Germany. Each fighter group was assigned grid portions to be strafed when a mission called “Jackpot” was ordered. These missions were targeted to destroy trains, barges, marshaling yards, convoys, airfields, etc. They were considered targets of opportunity. Occasionally, fighters were ordered on Jackpot raid when there were no bomber missions. Later, following the invasion, specific areas were ordered attacked.

DID YOU CARRY BOMBS?

Either 250- or 500-pound bombs could be loaded, one under each wing.

WHAT TYPE OF PLANNING WAS NEEDED FOR THESE MISSIONS?

After the invasion, a red line showing our general ground force position was marked on the squadron battle area map. North and east of this line we could see targets of opportunity. I flew quite a few such missions in June and July 1944. We worked well away from allied troops to minimize the chances of “friendly fire” incidents. Detailed planning was not required on most strafing missions. It was done with eight-plane sections: four planes would attack and four would give protective cover. The flights rotated in these assignments. Prior to this time, I had never worked with ground radar as a source of information. However, on one mission, radar knew who and where we were and radioed to inform me that I had “Thirty-plus bandits coming to visit.” I didn’t like the odds so we left to fight another day.

WHAT DO YOU RECALL ABOUT THE COLORS ON THE P-51S?

I remember the olive drab color. Later the planes were not painted and the bare metal was left exposed. There was nothing unique in the painting of the planes I flew. I don’t remember British dark green colors on our P-51s; all I remember was olive drab. I believe a block of code was assigned to the 357th FG. Code letters were then assigned by group operations to each of the three squadrons. All 363rd Squadron planes were given the “B6” code. This designation was followed by the individual assigned aircraft letter, in my case “G.” So both my assigned aircraft were B6-G.

WHAT WAS YOUR RADIO CALL SIGN?

All 363rd Squadron pilots responded to the name “Cement.” Each pilot was identified by a specific number. Mine was “Cement 99.”

WHO WERE YOUR GROUND CREW AND WHAT WERE THEIR DUTIES?

Staff Sgt. James Loter was my crew chief and the armorer was Cpl. Cunningham. I didn’t get to know Cunningham well but I did enjoy Jim Loter’s company during group reunions. I believe he was a typewriter mechanic during peacetime. If so, his background fit into his military duty of maintaining a fighter aircraft in top mechanical performance. Maintaining the P-51 was his primary responsibility. He did a very good job. He had been promoted to the highest rank that his position of responsibility would permit. I cannot ever remember when my aircraft was listed as unserviceable, except for scheduled maintenance. As for invasion stripes, I remember seeing striped P-51s on the ground as I returned on a mission the evening of June 5. Apparently I didn’t think much about it at the time. Upon landing I was told a briefing was to be at 11:00. I remarked “Well, we get to sleep in.” The answer was, “Briefing is tonight, not tomorrow morning!”

WHAT ARE YOUR MEMORIES OF D-DAY?

Within the 24 hours comprising D-Day (June 6, 1944) I flew several missions. My total combat time logged was over 12 hours. The main mission took off about 2:10 a.m., a night mission. It required flights, squadrons and the group to form into a cohesive force after penetrating a local overcast of low clouds. Our designated area to patrol was the Bay of Biscay. However, I could not form up my flight even after circling Leiston Airfield several times. I found a single plane so I took a wingman’s position. Another plane found us and joined up. We climbed out and headed to the assigned patrol area that night as a three-ship formation. Later, we passed over a large reddish area under a lower cloud deck (denoting antiaircraft and artillery gunfire). I presumed the area was Cherbourg. With daylight came improved visibility. I could see the unknown flight leader trying to orient himself. Good luck! This flight stayed on patrol for over seven hours. Upon return to Leiston, out stepped the unknown flight leader. It was Col. D.W. Graham, the group commander! The wingmen were Capt. C.E. Anderson and myself, both flight leaders without flights. It could have been worse if an unprotected wing of the airborne division had been subjected to air attack. We had aircraft scattered all down the southwest coast of France and into Spain. However, almost everyone returned to Leiston. The sheer number of allied aircraft shown on German radar probably influenced their decision not to commit their fighter force. Our invasion work was good; it just got off to a poor start. The bad start was due to inexperienced leadership at fighter command, wing, group, and squadron levels. Flying night formation in a single-engine short exhaust stacked aircraft was not the best idea. The P-39, P-40 and P-51 all suffered night formation problems because they all had short exhaust stacks. That made for extreme glare at night. The problem was so bad that night formation in any numbers greater than four should not be expected. P-38s and P-47s did not create glare as their exhaust gases were collected in rings or tubes to power superchargers. So groups equipped with Lightning’s and Thunderbolts should have performed as expected. About 10 a.m. on June 6, all three squadrons started two flights of eight planes each in independent operations. Our mission was to destroy German units encountered on the communication network in France. one section comprised eight planes was being refueled and rearmed while its companion section strafed and bombed German troops. I have no accurate information as to how many such missions were flown. I believe it was a week or two before we again operated as bomber escorts in group strength. By this time the US 9th Air Force and the RAF 2nd Tactical Air Force had units on the ground in France.

WHO WERE THE OTHER PILOTS YOU MOST FLEW WITH?

My flight was originally composed of Bob Moore, Al Boyle, Bill McGinley and myself. Supplementing these were L.D. Wood and Bob Foy. Later we welcomed Kenny, Roper, Franklin, Pearson, Orminick, Childs, Siverts, and Sullivan as replacements. Casualties within the flight were severe. There were many men whom I flew with that may not be well known. Jack Cleland, Monty Throop, Ed McKee, Joe Pierce, “Daddy Rabbit” Peters, Irwin Dregne, Tommy Hayes, John Storch, Dave Perron, Jack Warren, Pappy Medoris, R.D. Brown, Don Bochkay, etc. Their names could just as easily fill any book about WW II air combat but their names are not as well recognized as the Petersons, Englands, Carsons, Andersons, or Yeagers.

CAN YOU RECALL ANY OF THE NAMES OR MARKINGS ON THEIR AIRCRAFT?

The one I remember best is Bill McGinley’s plane, named “Typhoon McGoon.” I believe that Foy flew “Reluctant Rebel.” Peters’ airplane was “Daddy Rabbit.” Bud Anderson named his “Old Crow.” I was uncomfortable flying “Old Crow” in fear that I may have to abort a mission. You knew when flying Anderson’s airplane–no aborts–the plane was not a problem.

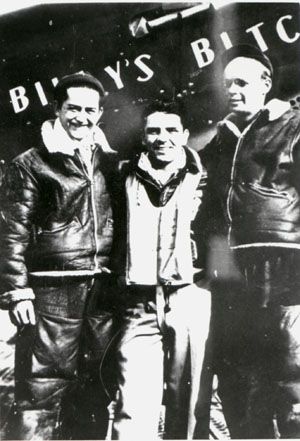

HOW WAS YOUR AIRCRAFT NAMED “BILLY’S BITCH”?

The name was a holdover from the days we flew P-39s. I chose the name as appropriate for my first P-39. Beautiful to behold, clothed in style, passionately sensitive to a gentle touch but absolutely unforgiving when not receiving full and proper attention…truly the definition of a bitch and a P-39! Jim Loter probably painted it on my P-51. My P-51B had a woman’s head painted on the plane’s left side only. The name “Billy’s Bitch” appeared on both the left and right sides. (Referenced from sitting in the planes cockpit) My P-51D had the name “Billy’s Bitch” lettered on both sides. Lettering for Billy’s Bitch was white on both aircraft. Both B and D displayed 6 victory markings. All my victories were in the P-51B.

HOW DID YOU RETURN TO BASE IN BAD WEATHER?

When solid clouds obscured England and the sea, we got a radar heading to home and an estimate of the cloud base at Leiston from “Earlduke”, our ground support unit at Leiston. This information was used by the flight leader to make an instrument letdown to get below the cloud deck. The flight flew formation on the leader. the leader flying on instruments proceeded down to the minimum altitude at which he would expect to see the surface. At this point the flight should be able to proceed by visual reference. The only problem than was to correctly judge where the sky-water contact point was. Sometimes the sea and haze had about the same color, making it difficult to discern which was water. I made this type of letdown to a 500- foot elevation, and BELIEVE ME–THIS IS NO WAY TO RUN AN AIR CORPS. As a flight left a recognized landmark on the continent, a general heading for England would be followed. This was based upon the flight leader’s identification of a landmark. As an example, from the Zuyder Zee or Dutch Islands, steer west or 270 degrees to encounter England. From Cape Gres Nes steering about 320 would get you home. From Cherbourg to north til you hit land. I flew combat from February til August 1944. During that time the Army Air Corps did not employ either the equipment or procedures to safely return fighters to their bases during inclement weather. During this time the RAF was using a ground controlled approach (GCA) system to aid returning fighter aircraft. I learned of this from an RAF pilot who flew with the 363rd FS in our group. No specific provisions for equipment, planning, or personnel were in place to assist pilots with the problems of navigating to airfields and avoiding midair collisions. A radar intercept from Earlduke could give you a direction bearing only to Leiston, and the local ceiling. At the time, that was the only procedure we could employ to get our men home. I maintain that attempting to fly in poor weather with the procedures employed, resulted in considerably casualties for all air forces.

HOW DID YOU RECOVER A FLIGHT OF AIRCRAFT?

When no air combat occurred, we maintained tactical formation during a mission. Runway approach was made by flights. We approached at a minimum altitude and the formation was echelon right. This permitted a “widow maker” peel off type of pattern for landing. Using the widow maker approach minimized the exposure time, that period when a plane was unprotected during a landing pattern.

DID YOU DO ANYTHING DIFFERENT THE DAYS YOU CLAIMED A VICTORY?

No! I harshly criticized my best wingman, Capt. Bob Moore, for slow rolling his aircraft over the airfield after a kill. I told the victorious Moore, “We don’t show off and foolishly endanger an airplane and its pilot.”

DID YOU PARTICIPATE IN ANY AIR-SEA RESCUES?

Yes, once when an unfortunate midair collision involved Bill McGinley and Santiago Gurierrez. I called a Mayday in hope there were survivors. A British Spitfire joined me circling over the visible smoke created by the wreckage of the aircraft on the sea. The Spit pilot motioned that there were no survivors. I agreed. A very sad day for all concerned.

HOW DID YOU FLY ALL YOUR MISSIONS WITH AN INJURED ARM?

I had a lot of HELP! We were stationed at Oroville, Cal., during 1943. Al Boyle, my assistant flight leader, shot me by accident. The .45 cal. bullet went through my upper right bicep without causing bone damage. The injury was to the nerves and muscle in the arm. After hospitalization and being grounded, I walked around with my arm in a sling for about a month. My right hand was inoperative. The medical decision was to let nature take its course. If the nerve endings rejuvenated themselves to restore feeling, I had a chance to be of use to the group. John Bricker Meyers was the 363rd Squadron’s intelligence officer and a lawyer by trade. He had a briefcase full of courts martial papers that remained unfiled. Boyle’s papers were among the many that remained in the briefcase. Thanks here to John Bricker Meyers. No one said a word to me as to my future. Don Graham was my squadron CO. When I was shot I bled all over his pants and ruined them. He was in the ambulance as I was taken to the field dispensary. I owe him a lot, not only for the slacks, but I’m sure he knew what Meyers was doing or not doing! Thanks, Gen. Graham. While recovering I did a little work at group operations until the group moved to Casper, Wyoming, and then to Camp Shanks, a staging area for shipment to Britain. Lt. Col. Edwin Chickering, the group commander, called me to his office and said, “Obee, you know you don’t have to go with us.” I replied, “Sir, I’d come too far to turn back. I want to go if only to hold somone’s hat.” He said, “You are dismissed.” A thanks to Col. Chickering. I made it on and off the Queen Elizabeth without assistance. I wanted to prove to myself that I was not helpless, and that I could do fine using one arm. At Raydon Wood, our first English base, I could shovel mud with the rest of the guys. My fingers were numb but my arm motion was returning. Now, the problem was what to do with me. The group did little flying during my recovery period because of transfers to different bases. I knew that if I didn’t log some flying time soon I would lose flight pay. The group needed pilots, not observers. Soon the group would receive new airplanes and combat could not be far behind. There was only a Taylorcraft L-4 on the flight line at Raydon Wood. Maj. John Barker, the group flight surgeon, drove with me to the closest general hospital for medical evaluation. The evaluation was to be performed by a neurologist. This particular neurologist was a captain. After demonstrating to him that my freedom of motion was acceptable, he put me through two hours of uncomfortable sensitivity testing. He then asked me to leave the room. When I left, I managed to keep the door ajar so I could listen to what was going on. I heard this specialist tell Maj. Barker in effect that I should be sent to the US for discharge. He felt I was medically unfit for duty. I had never heard a captain speak to a major in this manner. I left the hospital with Maj. Barker, and when we got into the jeep I asked “What are we going to do?” He looked down and asked, “OBee, can you fly an airplane?” I replied, “Yes, sir!” He said, “Go and fly.” Somewhat startled, I asked, “What about that captain of neurology?” Maj. Barker said, “He don’t fill out the forms. I do.” May God forever bless John Barker, MD. I owe him big time; what a wonderful demonstration of medical judgment. I was flying the L-4 that afternoon. Physically I may have encountered trouble pulling the emergency canopy release and the D-ring on the parachute in an emergency. Early in 1944 the first two fingers of the right hand were numb and I’d have to use my left hand to fire the guns. However later in the year all fingers had some feeling. Remember that it does not take great physical strength to fly an airplane. The RAF fought using a pilot without legs and one with his left arm missing.

HOW DO YOU VIEW YOUR WW II EXPERIENCE NOW?

Considering the overall experience of WW II on me, I view myself as being lucky not only to be alive but also wonderfully pleased to have been associated with some of the finest men this nation ever had to offer the world.

Rare still shot of P-51B “Billy Bitch” taken from a WWII movie camera film.