Headed into the wind for maximum engine cooling, the 362nd FS awaits its turn to take off. The aircraft at left Nooky Booky IV is that of Major Leonard Carson, top scoring ace of the 357th FG. Photo Merle Olmsted

THE GREAT MOUSETRAP PLAY

By Merle Olmsted

“From then on, the mission was uneventful.”

So ended the combat report of Lt. Col. Andrew Evans who had just shot down four Luftwaffe fighters in the damndest rat race the 357th Fighter Group had ever been involved in. It was the 14th of January 1945, and Nazi Germany was dying the death it had inflicted on so many others. Still, there was a great deal of fighting to be done. On the ground, the last major Nazi effort to turn back the invading Allied armies, with a powerful surprise offensive on the US 1st Army, through the Ardennes, was shuddering to a halt. General von Rundstedt’s 18 divisions had scored impressive early successes, but by the end of December 1944 the momentum was gone. Slowed by desperate resistance of scattered American troops, and battered by an incredible array of Allied tactical air, the Battle of the Bulge was near its end.

In the air the 8th Air Force was at the peak of its awesome power, and had flown the largest mission in history on the day before Christmas when over 2,000 B-17s and B-24s had applied their weight to stop the German offensive.

The rampaging US 9th Air Force and the RAF’s 2nd Tactical Air Force had made daylight movement of German transport an extremely hazardous proposition, and this was one reason the Luftwaffe had laid on a massive strike, in hopes of blunting Allied tactical air. This operation was launched on New Year’s Day by nearly 800 Nazi fighters against Allied airfields on the continent. Though the attackers scored heavily in some areas, they lost even more to defending fighters and AA guns.

Such was the general situation at the end of January. The weather had been foul throughout Europe, and there were many days when flying was all but impossible. At bases scattered across England, hundreds of fighters huddled under their canopy covers, shrouded in mist and freezing rain. Hundreds of equally miserable mechanics trudged to their aircraft every morning in early January to chip ice from the wings, crank and warm stubborn engines, only to cover them again and dash for the meager warmth of line shack or Nissen hut.

However, 8th AF weather forecasters became aware that an impending change would occur about the 10th of January. A high pressure center was forming over northern Sweden and Finland, while another was taking shape in the North Atlantic west of Ireland. These two high pressure centers soon joined, producing a long ridge from the North Atlantic to Russia. This, in turn, tended to divert storm centers north of the British Isles, and brought dry, cold air over northwest Europe.

By the 14th the weather was ideal for what became “The Big Day” in 357th history, resulting in the largest number of enemy aircraft shot down by one group, in one day, in 8th AF history.

With their part ended in the Ardennes affair, the heavy bombers of the 8th AF were again ready to return to their strategic bombing mission, and on the 14th over 600 “heavies” from the 2nd and 3rd Divisions were to bomb oil targets in northwestern Germany.

The 357th, in residence at AAF station 373 near the towns of Leiston and Yoxford, had long since become a veteran outfit. Blessed with excellent leadership and equipped with the superb P- 51 Mustang, it had flown 252 missions (mostly bomber escort) in 11 months. Its pilots had been credited with 517 victories and there were 39 aces on its roster.

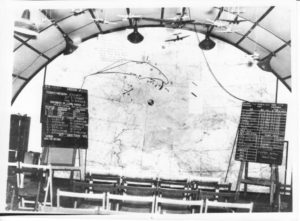

Briefing room for 14 Jan 45 Mission

When 8th AF Field Order 1515A clattered in on the teletype in the early morning of the 14th there was nothing to indicate that it would be much different than the previous 252 missions, though takeoff time was somewhat later. When the first pair of Mustangs lifted off Leiston’s runway it was 1010 hours. Riding in the lead was the group commander, Lt.Col. Irwin Dregne, in his P-51 “Bobby Jeanne.”

There were 66 red-and-yellow nosed Mustangs at takeoff, 22 each from the 362nd (Dollar), 363rd (Cement), and 364th (Greenhouse) Squadrons. However, three of those landed again due to various troubles, and seven others turned back before the group was committed, so the force had dwindled to 56 at the time of rendezvous with the leading bombers of the first three combat groups, north of Cuxhaven at 1150.

The target was Derben, a small city northwest of Berlin, and the force made landfall at Cuxhaven one minute after noon as the Mustangs slid into their escort positions. As the armada moved inland the low, broken clouds over the North Sea gave way to CAVU conditions as the 8th AF forecasters had predicted.

As the first force neared the target with the B-17s at 24,000 feet, the 357th escort was as follows: on high cover at 30,000 and somewhat farther back on the bomber stream was the 363rd Squadron, led by Major Robert Foy. Providing close support at about 26,000 were the remaining two squadrons. With the target coming up on the horizon, the mission leader and the squadron leaders were especially alert for a tactic they had been warned of. This report, the result of POW interrogations, had alerted all groups that the Luftwaffe was about to try the “company front” assault. Although not a new tactic, there were indications that it was to be tried on a larger scale.

Seen here in the fall of 1944 is a flight of the 364th FS. The machine nearest the camera is Richard Peterson’s C5-T, Hurry Home Honey, with John Storch’s The Shellelagh. Third in line, a B type is Pappy’s Answer.

Twenty miles north of Brandenburg the group leader, Colonel Dregne. spotted two large gaggles of e/a approaching the lead box of bombers from 1 o’clock high (roughly from the southeast). It was 45 minutes past noon. taking Greenhouse Squadron with him, he turned to intercept, but then spotted a third group of e/a at his own level. The two large gaggles whose contrails he had spotted first were now seen to be perhaps 100 Me-109s on top cover at about 32,000 feet. Ignoring them, Dregne ordered Greenhouse (364th) to drop tanks, and the 18 Mustangs turned into the low gaggle, which proved to be FW-190s in the expected company front waves of about 18 aircraft each. the 190s immediately abandoned their company front formation, most breaking right into a Lufberry, and one of the biggest fighter battles of the war was on.

Dollar Squadron (362nd) led by Major John B. England (already a triple ace) had dived into the middle of the mixup, setting up the mousetrap play that had been hoped for. Although a tactic as old as war, it worked again and drew the Me-109 top cover into the battle, leaving the remaining 363rd Squadron free to spring the trap.

From this point it is not possible to follow the ratrace in any order, because the P-51 formations broke up about the time the 190 company front disintegrated. However, formation discipline held up well in that most wingmen were able to stay with their element leaders, and in the 362nd only one pilot returned alone.

From the group leader’s mission report and the encounter reports of individual pilots, it is possible to glimpse the action for the next 30 minutes. Colonel Dregne himself opened the combat when he fired at a 190, getting strikes on its tail and fuselage. Although it fell off in a spin, he did not see it again so claimed only a damaged. At this point he found himself in a Lufberry with 8 or 10 FWs. He managed to climb above them, went to the aid of a bomber box under attack, and found a stray P-51`which turned out to be Andy Evans. Dregne, who had long since lost his wingman, ordered Evans to fly his wing and the two of them again took up escort duty.

Previous to this chance meeting with the group leader, Evans had got more than his share of the action. Though deputy group CO, Evans had been a spare when the mission took off, but at rendezvous Lt. “Dittie” Jenkins, flying White Two of the 362nd, turned back with a rough engine. White Three was detached to escort him home and Evans moved into White Flight where he stayed until, as he put it, “all hell broke loose.” In quick order Evans shot down an Me-109 and a 190, faked another 190 into flying into the ground, then turned to engaged another FW which promptly “collided with somebody.” Then, “thoroughly shaken up,” he climbed to 31,000 where he joined Colonel Dregne on withdrawal support for the bombers. Soon after the two had joined, an Me- 109 was seen far below and Dregne shot it down in flames.

Colonel Irwin Dregne (left) who led the 14 January Mission. With him is Lt Col John Storch, who scored three times on “Big Day.”

Captain “Big John” Kirla of the 362nd also claimed four victories for the day while no fewer than six pilots claimed triples. One of the latter was Major Leonard K. Carson who was to end the war as top scorer of the 357th Group.

Major John Storch, leading Greenhouse Blue Section, claimed two 190s and a 109, the latter being unlucky enough to be shot down after Storch’s K-14 gunsight burned out. “I was a picture of confusion,” says Storch, “trying to turn, fire, fix my sight, put down flaps, pull up flaps, and work my throttle. Finally, after giving up on my gunsight, I once again got close enough so I couldn’t miss and got strikes; coolant and smoke came from the e/a. He tried to belly in just short of a forest, hit and bounced almost over into a clearing, but hit the last few trees…and the pieces scattered into the clearing. I claim one Me-109 and two FW-109s destroyed. Ammunition expended: 1,725 rounds.” (Note: the P-51D typically carried 1,880 rounds.)

Major Bob Foy was leading Cement Squadron and reported the following encounter: “The 190s dove toward the bombers and we attempted to cut them off, meeting them head-on just before they were in range of the bombers. The 190s broke their company front formation and headed in every way imaginable. I turned to the right and lined up a 190 closing in to a good firing position, giving him short bursts while in a shallow turn, and about a 30-degree deflection.

Strikes were observed on both wings and he immediately straightened out, flew level for a second or two when suddenly the pilot jettisoned his canopy and bailed out. This action took place at approximately 22,000 feet. I pulled up sharply to avoid colliding with the Hun pilot and as I flew directly over him, I observer another FW flying 90 degrees to my path and directly beneath me about 3,000 feet. I did a quick wingover and splitessed onto his tail. The pilot apparently saw me coming and did a splitess toward the deck. I followed, giving him short bursts observing strikes on the left wing. He continued his dive and must have been indicating better than 550. He made no more to pull out of his dive so I started a gradual pullout at about 4,000 but kept his ship in view off to one side. the e/a dived straight into the ground and I made a 360-degree turn, diving to get a picture of his ship burning on the ground. “I then leveled off and made a climbing turn toward the bombers and giving my flight an opportunity to pull up into the formation. My No. 2 man pulled up but somewhere en route and during the fun, I lost my second element.”

Foy and his wingman stayed with the bombers on withdrawal until low fuel and oxygen dictated heading for home. On the way they found a train and Foy shot its locomotive full of holes, chased a 190 which was lost in haze, and finally burned another 190 which he found parked on “a beat-up airdrome.”

Although the group leader’s mission report indicates the enemy force was composed of several hundred 109s and 190s, several Greenhouse pilots had an inconclusive encounter with a jet Me-262. Lt. Dale Karger spotted the 262 first, which was making a pass at the No. 2 Mustang in Maxwell’s Green Flight. The 262 pilot overshot, and Lt. Ray Banks, element leader in Green Flight, fired one burst at the jet but observed no strikes, and the 262 flew away.

Also out of the ordinary was the 109 that Lt. Charles Weaver became involved with early in the action. Another 109 had dived between him and his element leader, and while attempting to rejoin, he happened upon another 109 painted olive drag with black and white invasion stripes around the fuselage. Weaver immediately tacked onto his tail, firing a short burst at long range which forced the 109 into a steep left turn. From a semi- inverted position Weaver fired again, with no apparent results. Nevertheless, the strange OD 109 dived straight into the ground.

The big battle that day over the Berlin area was not exclusively a Yoxford Boys-Luftwaffe affair. The 20th Fighter Group, escorting combat groups farther back, claimed 19 1/2 victories, and the 353rd Group claimed 9 e/a shot down. It is a safe bet that the 361st Group was also there, as two 357th pilots had considerable trouble with yellow-nosed P-51s. Captain C.K. Maxwell had shot down three FW-190s and was about to engage a fourth when he looked back to check his tail and found a P-51 there. Feeling his tail was covered, he turned back to the 190 but immediately felt strikes on his own aircraft, and his canopy flew off. The yellow-nosed 51 then closed in, saw his mistake and flew away, leaving Maxwell with shot-up controls, no radio, coolant temperature against the peg, and belt of ammunition hanging out of one wing. A long way from friendly territory, Maxwell figured his chances were slim but discovered that, at 8,000 feet, the sick engine would produce a small amount of power and he eventually arrived over Antwerp at treetop level and bellied the flying wreck into a British Army parking lot.

The scope of the battle can be detected from the observations of the group leader. One surprising comment, considering the late date, is that some Me-109s were E models. Twenty-five miles north of Brandenburg an unidentified P-47 was seen to shoot down an unidentified P-51, and 15 minutes later three B-17s were shot down northwest of Berlin with only five chutes observed. A 20th Group P-51 was seen to shoot down a FW- 190 and then meet the same fate at the hands of another 190.Finally, a 357th pilot, in the heat of battle, fired on another 20th Group Mustang, observing strikes on the wing but this P-51 headed home apparently OK.

Five pilots of the 357th scored doubles and the total group claims for the day were an incredible 57 1/2. Lt. Robert Winks shared a 109 with a 361st Group pilot. One of this number was Foy’s grounded 190, but the other 56 1/2 were all air claims, a total unapproached before, or after, by any 8th Air Force fighter group.

Like most air combat claims, it is not possible to determine whether these were totally accurate. However, a perusal of all pilots reports for the 14th of January indicate that the large majority of the victims were seen to bail out, crash, or break up in the air. In any case, it is clear that the Luftwaffe had suffered a disaster at the hands of a small group of P-51s.

Lt Jim Gasser and his G4-K-bar, An element lead in the 362nd Green flight. Gasser shot an FW 190 off the tail of a P-51.

357th losses were just as amazing. Five P-51s failed to land at home base but one of those landed in Allied territory and soon returned to base. Another was Maxwell’s wreck at Antwerp. The three lost–Lt. George Behling of the 362nd and Lts. James Sloan and William Dunlop of the 363rd–were reported as last seen in the combat area but all survived and returned to Allied control at the end of the war.

It had been a day of astounding success, but for William Dunlop it was success of a different kind–survival of a catastrophic crash. Leading Blue Flight of Cement Squadron, he was involved in the general melee early in the battle, and then found himself on the tail of almost 30 109s at about 20,000 feet. He immediately engaged the tail-end Charlie. The rest of his story is best told from his encounter report filed months later: “I hit him repeatedly from wingtip to wingtip. the canopy flew off to the right and the pilot came out the same side, barely missing my wing as I passed between them and the smoking 109. One fraction of a second later, it felt as if my guns were firing without me pressing the trigger, and the controls wentout, completely dead. I watched one of my left-hand .50s blow out thru the wing skin and my fuselage tank caught fire. The ship was in a drifting dive and going straight in. The pressure held me in the right of the cockpit and was powerful enough so I couldn’t raise my hand to release the canopy. Then everything blew–wings, canopy, tail and fuselage separated and seemed to flow in different directions. The canopy must have left first, as I felt flame sucked in the cockpit, was cooked on the forehead and then felt the cool air as I was flown from the rest. I landed still in the bucket seat with armor attached and shoulder straps neatly in place. The engine and one wing lay together about 50 feet distant, and the pieces were still floating down all about. Another 100 yards distant lay the 109, ammo popping.”

Dunlop’s report leaves unanswered several interesting points, but it appears clear that he never used his chute, which would have been impossible as he was still strapped in his seat when he hit the ground. One can only speculate that the explosion which tore his P-51 apart must have occurred very close to the ground–close enough to arrest what would have been a high speed and surely fatal crash. Survival in such a crash, if not unique, must be extremely rare. It was indeed a “big day” for William Dunlop too! (His victory was not included in the 57 1/2 claimed for the day as he did not file his claim until after the war.)

By 1445 hours all returning aircraft had landed at home base. When the preliminary claims went in, there was considerable disbelieve at 66th Fighter Wing, and higher headquarters, but recounts came up with the same figures. Later, as the celebration continued at Leiston, a teletype message arrived from Lieutenant General Jimmy Doolittle (8th AF commander) who said, “You have given the Hun the most humiliating beating that he has ever taken in the air.”

Although never unbeatable, the Luftwaffe fighter force had seldom been a pushover, and it is appropriate to try to find the reasons for the lopsided defeat. Even at this late date, the Luftwaffe as still a potent force but it was running along the edge of its grave. Many of the experienced pilots and leaders were dead, and their replacements had received only sketchy training due to a lack of time, fuel, facilities, etc. On the 8th Air Force side, its groups were at the peak of their form, heavily laced with veterans, confident and aggressive, and flying one of the best fighters in existence. Equipment was surely a part of the story; the FW-190 and the ageing Me-109 were certainly excellent fighters, but the Mustang was simply better. Probably no other fighter group ever had a day as big as the 357th’s on 14 January 1945.

This article first appeared in the Journal of the American Aviation Historical Society, Fall 1974.